Names

Australian Placenames of German Background

Introduction | NT & WA | NSW | QLD | SA | TAS | VIC

South Australian Placenames of German Background

▶ See the list of place names in South Australia changed in 1918 during World War I (with locations and explanatory notes).

▶ Article about South Australian German place names:

Part 1 - The effect of World War 1 :: A complete report? :: Cape Bauer - the British Empire's gratitude

Part 2 - German place names that ‘escaped’ detection :: Place names as a recruiting tool

Part 3 - "German" names by accident? :: The 1930s - some German names reinstated :: A German place name that didn’t happen :: New German place names after 1918

German place names that ‘escaped’ detection

It seems possible that the bigger factor in names being identified for change was if they sounded German rather than their enemy origin. The following names were not identified by the Nomenclature Committee in 1916 and are of German origin or have a strong connection with Germany.

➽ The most surprising omission from the list of names with a German background is the capital of South Australia, Adelaide. The new city was named after a German princess who married the future king of Great Britain - from 1830 onwards she was Queen of Great Britain and Ireland as well as Queen of Hannover. Her name was Adelheid Amalie Luise Therese Caroline of Saxe-Meiningen. In England the spelling of her name was modified to Adelaide. You can read more about Queen Adelaide in this article. Why did the South Australian government not change the city’s name Adelaide, of ‘foreign enemy origin’? Perhaps it did not sound German enough.

The South Australian historian Ian Harmstorf is not sure if the committee simply overlooked the name or if they considered that changing Adelaide's name would be "too big a chestnut to handle".[1]

➽ Altona - Two subdivisions bear this name:

In 1866 Johann F.W. Mattner (1826-1876) subdivided land that he had bought earlier about two km east of Lyndoch in the Barossa Valley, and named it Altona. Mattner had arrived in South Australia in the ship Skjold on 27 October 1841 from the port of Altona, Germany. Altona is today the westernmost urban borough of the German city state of Hamburg.

In 1911 Samuel Bowering Marchant (1870-1950), a contractor[2] of the South Australian town of Balaklava, gave the name Altona to an area of land he owned in the region between Port Wakefield and the north-western edge of the Barossa Valley. His second wife was of German descent. In the words of the historian Geoffrey Manning, both places named Altona "escaped the notice of the committee appointed during World War I to erase German names from the map of South Australia".[3]

'Hamburg-Altona' sign on a platform at the railway station of Altona, Hamburg, Germany.

➽ Gnadenfrei / Marananga. This locality lies about 5 km north-west of Tanunda and was at first called Salz Creek (Salt Creek) by German settlers who arrived around 1848. The place soon became known as Gnadenfrei (meaning ‘free by the grace of God’), and the church is still called St Michael’s Gnadenfrei Lutheran Church. The people of Gnadenfrei in the middle of the 1800s were originally members of Pastor Kavel’s congregation at Langmeil, but established their own church at Gnadenfrei. The present-day church was built in 1873 and the tower and other features were added later. A German school was established in 1879. The Nomenclature Committee of 1916 did not include Gnadenfrei in their place names report for the government. In 1918 the locals decided to build a new school, and (perhaps due to the anti-German mood of the time) called it Marananga, and this name came into general use for the locality. In 1958 Malcolm and Joylene Seppelt (of the famous German wine-making family in the area around Seppeltsfield) established a vineyard at Marananga which they called Gnadenfrei Estate. The red wines produced from that land are highly regarded, though the new owners of the vineyard no longer market the wines using the name Gnadenfrei.[4]

The Gnadenfrei Lutheran Church at Marananga

A wine bottle - a wine produced by Gnadenfrei Estate

➽ Kroemer Crossing - the 1993 UBD map of the Barossa Valley marks Kroemer's Crossing as a locality close to Tanunda. It was named after Stephan Kroemer who bought land there on 25 September 1873. He was born around 1820 in Silesia (at that time part of the German kingdom of Prussia), and arrived in South Australia on the ship Victoria in 1848. Kroemer died on 27 August 1895 and is buried at Tanunda.[5]

Named after Prince Albert

➽ Albert Park is a suburb of Adelaide, 9 km north-west of Adelaide's city centre, on Kaurna Country.[6] It was named after Prinz Albert von Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha,[7] the German prince who married Britain's Queen Victoria (at birth his name was formally Prinz Franz Albrecht August Karl Emanuel von Sachsen-Coburg-Saalfeld). You can read more about why Australian place names honoured this German prince in this article.

➽ Alberton is a suburb 12 km north-west of the Adelaide city centre, on Kaurna land. It was first known as 'The Town of Albert' and then became 'Albert Town' which was shortened to Alberton. In South Australia Alberton is well-known as the home of the football club Port Adelaide FC ('Port Power'), which plays in the national Australian Football League.[8]

It seems that with place names like Adelaide, Altona and Alberton, if the name did not look very obviously German, its strong connection to Germany was not a problem.

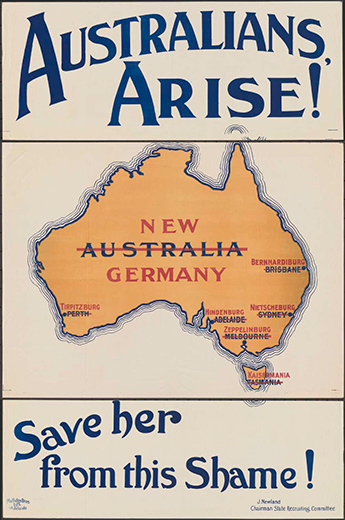

Place names as a recruiting tool

Army recruiting poster

Image source: Australia. State Recruiting Committee of South Australia & Newland, J & Halliday Bros. (1916). Australians arise! save her from this shame. National Library of Australia. Retrieved September 25, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151734357.

This poster was part of the effort to persuade more Australians to enlist in the army. It was produced by the recruiting office in Adelaide and claimed that Germany would change the names of Australia’s major cities if it were to occupy the country. For example this map changes the name Adelaide to Hindenburg, and changes the name Tasmania to Kaisermania. By the time this recruitment poster was produced (sometime between 1916 and 1918) it was in fact Australia that had already changed numerous place names since the start of the war – removing German place names from the map of Australia.

Who knows if Germany would have wanted to change place names in Australia – certainly Japan changed American place names and street names in the Philippines when it occupied those islands during the Second World War (they were a colony of the USA at the time). Among other streets, Taft Avenue and Dewey Boulevard got Japanese names. The Japanese renamed other places that they occupied, e.g. in the Micronesia part of the Pacific the island of Guam became Omiya Jima, and Wake Island became Odori or Ōtorishima.[10] When the Americans occupied Japan in 1945 they imposed American names on some streets and places, for example Washington Heights, and Doolittle Park.[11]

♦ Notes:

1. Harmstorf, Ian. (1981). The German Experience in South Australia. In: Insights into South Australian History, vol. 2, South Australia’s German History and Heritage. Historical Society of South Australia Inc. (1994) p.36

2. 'contractor' - the word means: a person who is hired to perform work or to provide goods at a certain price or within a certain time.

3. Manning (2012), p.34

4. Manning (2012), p.334 / Don Ross (local historian), personal communication, email, 14/10/2023 / Munchenberg, Reginald S et al. (1992). The Barossa, a Vision Realised. The Nineteenth Century Story. Barossa Valley Archives and Historical Trust Inc. p.195

5. Universal Business Directories Pty. Ltd. (1993). UBD Barossa Valley, Australia. Map 581 [cartographic material] : including Angaston, Kapunda, Lyndoch, Nuriootpa & Tanunda. Adelaide : UBD, a division of Universal Press. / Manning (2012), p.470 / Crawford, Ellouise. (2020, September 23). Kroemer’s upgrade comes full circle. The Bunyip. <https://www.bunyippress.com.au/news/kroemers-upgrade-comes-full-circle>. Accessed 16/12/2023. / Janmaat, Robert. (n.d.). 'Victoria'. The Ships List, <www.theshipslist.com/ships/australia/victoria1848.shtml>.

6. Manning (2012), p.21

7. Appleton, R., & Appleton, B. (1993). The Cambridge Dictionary of Australian Places. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139084970. p.3

8. Manning (2012), p.22

9. Harmstorf, Ian. (1994). A Trust Betrayed. In: Insights into South Australian History, vol. 2, South Australia’s German History and Heritage. Historical Society of South Australia Inc. p.65

10. Immerwahr, Daniel. (2019). How to hide an empire. A short history of the Greater United States. London: The Bodley Head. p.195

11. Immerwahr (2019), p.225

♦ References:

Manning, Geoffrey H. (2012). A Compendium of the Place Names of South Australia. From Aaron Creek to Zion Hill. With 54 Complementary Appendices. Available online here.

Nomenclature Committee's Report on Enemy Place Names. Parliamentary paper (South Australia. Parliament); no. 66 of 1916, pp. 1-4. Available at SA Memory, via State Library of South Australia, online here.