Names

Australian Placenames of German Background

NT & WA | NSW | QLD | SA | TAS | VIC

The British Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and Coburg

The historical background to Albert's name in Australia

Albert and Victoria

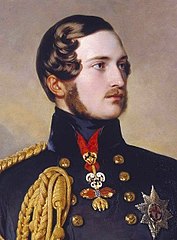

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, 1842

Painted by Franz Xaver Winterhalter

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The marriage of the German Prince Albert to the British Queen Victoria in 1840 resulted in Albert's name and his German background figuring in many place names in Australia.

Prince Albert (Albert von Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha), Queen Victoria’s husband, was a German prince, born at Schloss Rosenau near the town of Coburg (in the north of today’s federal state of Bavaria). Albert and Victoria were cousins, and the same German mid-wife, Charlotte Heidenreich von Siebold, had assisted at their births in London and in Coburg, Germany. Early in their marriage Victoria and Albert often spoke with each other in German. Victoria's mother, the German Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, and later (through marriage into the British royal family) Duchess of Kent and Strathearn, could not speak English very well. According to the English biographer and journalist A.N. Wilson, Queen Victoria was "more German than British"[1] and she referred to German as “the dear German language”.[2] The English historian Norman Davies wrote of Victoria: “[She was] conceived in Germany, married to a German, and completely surrounded by German relatives. Though educated in England, she spoke German by preference, especially with Albert and their children.”[3]

Albert promoted many public educational institutions and supported technological progress. Victoria and Albert were one of the most famous couples in history. The English historian James Hawes described Albert in 2018 as "one of the most politically influential Germans on the planet".[4] When Albert died in 1861 at the age of 42 there was much public sympathy for Victoria.[5] The English people had reacted coolly to Prince Albert when Queen Victoria married him.[6] For most Britons the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha was a small and not very significant state. It was only after Albert died that Britain acknowledged what he had done for the nation. There were very many obituaries in the British press - many of these seemed to express regret that "Albert had never been sufficiently valued during his lifetime for his many and notable contributions to British culture as an outstanding patron of the arts, education, science and business".[7] In the days before Albert's funeral the Duke of Argyll noted: "The whole nation is mourning as it never mourned before".[8]

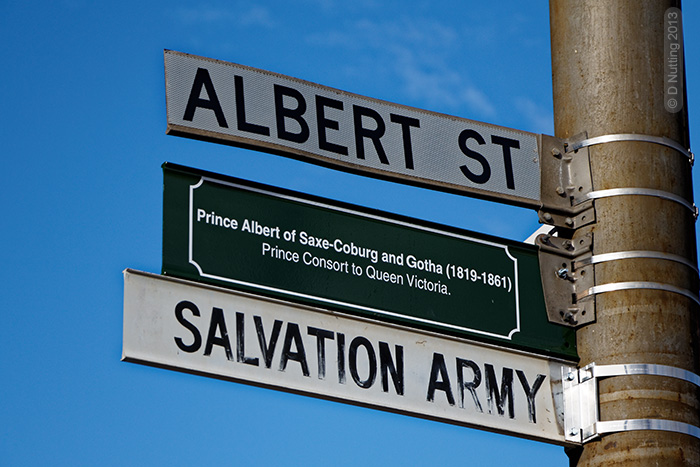

Sign of Albert Street in Brunswick, Victoria

Many places in various countries (particularly in the British Empire) were named after Albert, including towns, buildings, bridges, lakes and mountains. The English biographer A.N. Wilson wrote: "His statues were to be seen all over the Empire. Albert Halls, Albert Squares, Albert Streets filled every English-speaking town, and many of the towns in India".[9] Several places in Australia were named after Albert. As Eamon Evans wrote in his light-hearted book about Australian place names, Mount Buggery to Nowhere Else: “You can’t thow a rock in the former British Empire without it landing somewhere near a place which the Queen [i.e. Queen Victoria] said must be named after Albert.”[10]

In Australia there were also buildings named after Prince Albert. For example, at the time of the famous Eureka Stockade uprising on the Ballarat goldfields, and within Prince Albert's lifetime, there was a hotel at Ballarat East named the Prince Albert Hotel. It was run by two Germans named Carl Wiesenhavern and Johann Brandt. Carl Wiesenhavern was a good friend of the Italian digger Raffaello Carboni, who mentioned Carl in the famous book which he wrote about the Eureka uprising one year after the battle.[11] The Prince Albert Hotel no longer exists at Ballarat (and a Prince Albert Hotel in Williamstown (Victoria) closed in May 2024 after starting up during Albert's lifetime[12]), but there are Prince Albert Hotels in other parts of Australia.

Prince Albert Hotel in 2014. 254-256 Wright Street, Adelaide, South Australia.

Photo source: National Trust of South Australia, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr.

On the goldfields of Bendigo (Victoria) Jacob Cohn registered a claim in 1868 on behalf of the Prince Albert Company, on a gold-bearing reef that the company named Prince Albert Reef.[13]

Coburg

Queen Victoria felt a close connection to the German city of Coburg, as her mother, her husband and her uncle had all been born there. Victoria visited the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha with Albert more than once, and in September 1862 after his death she visited it again, in honour of him. She wrote of her affection for Coburg and for the German language in a letter to one of her daughters.[14]

Schloss Ehrenburg in Coburg. Whenever Prince Albert and Queen Victoria visited his hometown of Coburg, they stayed in this palace.[15]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Überfranke

An inner Melbourne suburb has the name Coburg.

The Cobourg Peninsula (N.T.)

The Cobourg Peninsula is a remote peninsula 350 kilometers east of Darwin in the Northern Territory of Australia. The peninsula and some off-shore islands make up the Garig Gunak Barlu National Park.

Phillip Parker King, a young Royal Navy captain, named the Cobourg Peninsula after Prince Leopold Georg Christian Friedrich of the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg. Captain King commanded the ship HMS Mermaid on a surveying and exploration voyage on the northern coast of Australia during the first half of the year 1818. Phillip Parker King published a book about his voyages, which states for the date 29th April 1818: "The peninsula thus formed was honoured by the appellation of Cobourg, after His Royal Highness Prince Leopold."[16] (This misspelling of the German name Coburg appeared in the published book in 1827 and stuck.[17] ‘Cobourg’ is a French variant of the spelling.)

A stamp released by Australia Post in February 2021, showing a scene from the Cobourg Peninsula

The stamp in the photo is one of a series of four stamps that celebrate Australian wetlands that are protected under the international Ramsar Treaty. Australia was one of the 21 founding members of the treaty organisation and the Cobourg Peninsula was the first Ramsar site in the world in 1974.[18]

😕 Why did a Royal Navy officer name this peninsula after a prince from a small German duchy? When the Duchy of Sachsen-Coburg was overrun by Napoleon’s troops during the Napoleonic Wars, Prince Leopold joined the Russian army and became a successful officer. From 1814 he lived in the UK for a few years and was well-known in London. In 1816 he married Princess Charlotte of Wales, who was second in line to the British throne (and the daughter of Princess Caroline of Brunswick). Princess Charlotte died only a year later after giving birth to a stillborn son. When Belgium became independent from the Netherlands in 1830, the Belgian National Congress invited Leopold to become the first king of the Belgians. He was King Leopold I. of Belgium for the rest of his life. His niece, with whom he had a close relationship, became the famous Queen Victoria of Great Britain in 1837.

The names of several places, parks etc in Australia can be traced back to Prince Albert and his hometown of Coburg in Germany.

Sign naming Albert Park at Cootamundra, New South Wales.

In 1878 the Cootamundra townspeople named Albert Park in memory of Prince Albert.[19]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Mattinbgn

♦ Notes:

1. A.N. Wilson, in: Real Royalty. (2020, Jan 20). The secrets inside Queen Victoria's diaries.

2. Wilson (2019), p.XII

3. Davies, Norman. (2000). The Isles: A History. Revised edition. London: Papermac. p.631

4. Hawes, James. (2018). The Shortest History of Germany. Exeter: Old Street Publishing (paperback edition). p.98

5. Monteath, Peter (ed.). (2011). Germans: travellers, settlers and their descendants in South Australia. Kent Town (S.A.): Wakefield Press. Introduction, p. X (Roman 10)

6. Rappaport (2011), p.17

7. Rappaport (2019)

8. Rappaport (2011), p.109

9. Wilson (2019), p.5

10. Evans, Eamon. (2016). Mount Buggery to Nowhere Else : The stories behind Australia's weird and wonderful place names. Sydney (NSW): Hachette. p.80

11. Carboni, Raffaello. (1855). The Eureka Stockade. Melbourne : J P Atkinson and Co. p.68

12. Dmytryshchak, Goya. (2020). Last drinks at the pubs of Williamstown. Maribyrnong & Hobsons Bay Star Weekly. Accessed on 03/02/2025 from <https://maribyrnonghobsonsbay.starweekly.com.au/news/last-drinks-at-the-pubs-of-williamstown/>

13. Cusack, Frank (editor). (1998). Bendigo - the German Chapter. Bendigo (Victoria): The German Heritage Society. p.239

14. Doppler (1997), p.119

15. Ehrenburg Palace (in Coburg), Bedroom of the Duke. Website of Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung (Bavarian Palace Administration). Accessed on 09/12/2023.

16. King (1827)

17. Allen, Jim. & Australasian Society for Historical Archaeology. (2008). Port Essington: the historical archaeology of a north Australian nineteenth century military outpost. Sydney : Sydney University Press in association with the Australasian Society for Historical Archaeology.

18. The Ramsar Convention Secretariat. (n.d.) Ramsar sites around the world. In the website of the Ramsar Convention.

19. Main, George V. (2005). Heartland : the regeneration of rural place. Sydney : UNSW Press. p.135

♦ References:

Doppler, Julia. (1997). Queen Victoria and Germany. PhD thesis. University College London. Available online here.

DW Deutsch. (2019, August 24). Königlicher Auftritt: Albert und Victoria in Coburg | Euromaxx. [Video]. YouTube. (In German.)

King, Phillip Parker. (1827). Narrative of a survey of the intertropical and western coasts of Australia : performed between the years 1818 and 1822. Volume 1. London: John Murray. Available in digital format at Project Gutenberg.

Rappaport, Helen. (2011). Magnificent obsession: Victoria, Albert and the death that changed the monarchy. New York: St Martin's Press.

Rappaport, Helen. (2019, March 4). Prince Albert: the death that rocked the monarchy. History Extra (The official website for BBC History Magazine and BBC History Revealed).

Real Royalty. (2020, January 20). The secrets inside Queen Victoria's diaries. [Video] YouTube <www.youtube.com/watch?v=9rXmC2j3rS8>

Wilson, A. N. (2019). Prince Albert: the man who saved the monarchy. London (UK): Atlantic Books.