Names

Australian Placenames of German Background

Introduction | NT & WA | NSW | QLD | SA | TAS | VIC

South Australian Placenames of German Background

▶ See the list of place names in South Australia changed in 1918 during World War I (with locations and explanatory notes).

▶ Article about South Australian German place names:

Part 1 - The effect of World War 1 :: A complete report? :: Cape Bauer - the British Empire's gratitude

Part 2 - German place names that ‘escaped’ detection :: Place names as a recruiting tool

Part 3 - "German" names by accident? :: The 1930s - some German names reinstated :: A German place name that didn’t happen :: New German place names after 1918

South Australia received its first German place name as early as 1802, 34 years before the colony of South Australia was founded. This was Cape Bauer, named by the famous English navigator Matthew Flinders (more on Cape Bauer later in this article).

The effect of World War 1

Perhaps the most striking event in the history of the naming of places in South Australia was the state government’s decision during the First World War to change en masse 69 place names considered to be of enemy origin. A significant proportion of South Australia’s population was of German descent or had been born in the German-speaking countries. Many villages and small towns, particularly in rural South Australia, had been established by German-speaking immigrants and had been given a German name.[1] As the numbers of South Australia’s war dead increased further and further from 1914 onwards, the presence of these German names on the map of South Australia was considered by many influential people to be embarrassing or hurtful and inappropriate.

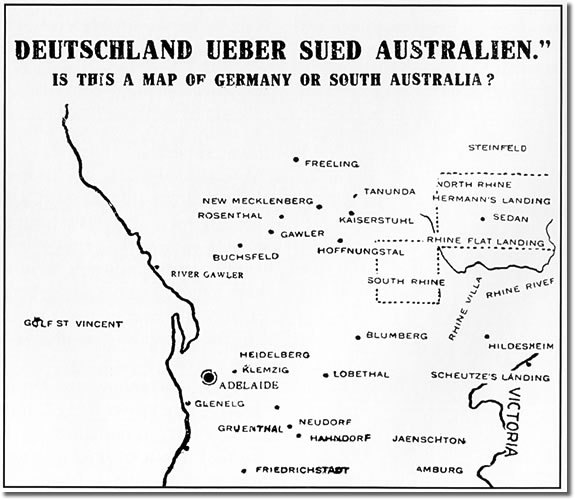

On 27th May 1916 the Adelaide newspaper The Mail created a map of part of South Australia and marked on it only the German place names and added the caption “Deutschland über Südaustralien – Some names that should be altered”.[2] The newspaper’s aim was to draw readers’ attention to the large number of German place names in the state. The picture below shows a copy of that map which the Sydney newspaper The Mirror of Australia reproduced three weeks later. That Sydney newspaper commented: "That these names should still stand nearly two years after we have been at war with Germany is an indication either of the influence of Germans in South Australia or of extraordinary tolerance on the part of British residents."[3] The Mail in Adelaide wrote: “The time has, however, arrived for South Australia to take stock of the German names which figure on her maps”.[4] The article did however acknowledge that German settlers had done a lot for the state and claimed that few people would want every single German place name changed (later this was the aim of the government, however).

Map: The Mirror of Australia, 17th June 1916, page 3

The Mail demanded that the place name Sedan be changed. Sedan is about 30 km east-south-east of Angaston, and the German settlers who founded the town named it after the battle of Sedan in France, when the Prussian army defeated the French in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War. The Mail wrote: “Although Sedan is French, the South Australian town was no doubt so designated at the instigation of German settlers, and an alteration should be effected. It is an insult to our glorious Allies (…) Sedan must disappear from local geographies.”

At the end of the article The Mail presented its readers with a long list of some of the German place names in the state. The Mail made a couple of mistakes, however. The list included Lochaber, which is a Scottish place name, and Veitch River – Veitch is also a Scottish name originally via Old French.

A week later The Mail reported in its next edition that many readers had reacted with surprise and indignation to its map showing German place names, judging by the letters that the newspaper had received. The paper reported: “Widespread astonishment has been caused by the revelation in The Mail of the extent to which German names have been bestowed on places in South Australia.” The place name Kaiserstuhl (meaning ‘The Emperor’s Seat’ – see 'Kaiserstuhl' in the list of place names changed in 1918) was considered particularly distasteful. The paper commented: “It would be hard to conjure up the thoughts of a soldier returned from France as he studies a map of South Australia and sees Kaiserstuhl.”[5]

A sign in the wine-producing village of Eichstetten am Kaiserstuhl on the eastern edge of the Kaiserstuhl mountain range. Like the Kaiserstuhl mountain in the Barossa Valley, the Kaiserstuhl mountain range in the Baden region of south-west Germany overlooks vineyards. The Badische Weinstrasse is the Baden Wine Route, a 500 km long wine-tourism route that goes past the Kaiserstuhl.

Photo source: Colin Smith, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The South Australian government appointed a Nomenclature Committee, a group of experts on place names, to examine the maps of South Australia and identify place names of “foreign enemy origin”. The government also asked the committee to suggest new names of British origin or preferably of Indigenous Australian origin to replace the ‘German’ names. The committee’s report was printed as Parliamentary Paper no. 66 in 1916 and there was a lot of debate about the report in parliament.

An extract from the report of the Nomenclature Committee of the South Australian Government in 1916 on enemy place names:

…the time has now arrived when the names of all towns and districts in South Australia which indicate a foreign enemy origin should be altered, and that such places should be designated by names either of British origin or South Australian native origin… We find, from a careful examination of the official records, that there are on the map of South Australia at least 67 geographical place names of enemy origin, ranging from an important centre like Petersburg to trigonometrical stations and obscure hills in the remote interior. There may be a few not officially recorded which have escaped our notice.

Nomenclature Committee's Report on Enemy Place Names, p.1

Sometimes governments don’t act on all recommendations of their expert committees, and this was the situation in this case too. The Nomenclature Committee suggested Indigenous names for all names that had to be changed, but in the time between the publication of the report in 1916 and the passing of the law which made the new names official in 1918, the government had changed in South Australia. The new government led by Archibald Peake ignored many of those Indigenous Australian names and instead produced names of battlefields in France where Australians had died (such as Verdun, or Cambrai), or the names of British officers (e.g. Birdwood), or well-known war names taken from Belgium and Palestine, ‘in a general rejection of the Committee's recommendation of Aboriginal names’.[6]

The place name changes made by South Australia's Nomenclature Act of January 1918 made up 76% of place name changes that occurred in Australia during the First World War.[7]

A complete report?

The Nomenclature Committee admitted in their report for the government that they were uncomfortable about changing the names of districts which were named after Germans and descendants of Germans who had done great public service for the colony and later State of South Australia (for example, the place name Hundred of Krichauff, and the Hundred of Schomburgk). However, the Committee members felt that it was “their duty to eliminate every name of foreign enemy origin”. Identifying these place names was no doubt a difficult and time-consuming task, due to the significant involvement of Germans over the preceding decades in many walks of life in South Australia and in many places, particularly in rural South Australia. The result of their search for place names of enemy origin seems inconsistent or uneven, as follows:

▶ They not only identified towns and districts (as requested by the South Australian parliament in August 1916), but also remote hills in the outback and even submerged oceanic rocks which were likely unknown to most South Australians in 1916.

▶ The German names of several landing places on the River Murray and on the state’s coast seem to have escaped the notice of the Committee in 1916. Here are a few examples listed by the historian Geoffrey Manning: Fromm Landing[8], Habel Landing[9], Hermann’s Landing[10], Kroehn Landing[11], Preiss Landing[12], Schlink Landing[13], Schuetze's Landing[14].

Two of these landing places on the River Murray, Hermann's Landing and Schuetze’s Landing, were marked on the map that the newspaper The Mail had created in its edition of 27th May, and you would think that the members of the Nomenclature Committee would have seen that article in The Mail (it attracted the interest of a Sydney newspaper as well). It is surprising that the Committee’s report later in the year did not include the names of these landing places named after German settlers. Perhaps they were in fact examples of places (in the words of the Committee) that may “have escaped our notice”.

▶ The Committee did not list the well-known name of the suburb of Alberton, which was also of ‘enemy origin’, being named after the German prince who married Britain’s Queen Victoria in 1840.[15] The English historian James Hawes described Prince Albert as "one of the most politically influential Germans on the planet".[16] You can read more about why Australian place names honoured this German prince in this article. Other place names of German origin like Alberton, and which were not included in the Committee’s report, are listed later in this article.

The Nomenclature Committee admitted in their report for the government that they may have missed one or two names of German origin that were not official names. They had in fact missed a few, but some of those were quite official place names (see the short list later in this article).

The state government did not, by the way, change the (French) name of the town Sedan, a change which the newspaper The Mail had demanded on the 27th May 1916.

The Sedan Hotel, in Sedan, South Australia.

Photo source: Mattinbgn, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Cape Bauer - the British Empire's gratitude

Some names were changed that were in fact in a remote location and probably not well-known to many South Australians and had historical significance because of their relevance to early British interaction with South Australia, for example Cape Bauer. Cape Bauer lies north-west of Streaky Bay, and about 470 km north-west of Adelaide, and was named by the famous English navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders in 1802 after Ferdinand Bauer, the Austrian botanical artist who was one of the scientists on board Flinders’ ship HMS Investigator.[17] In the days before photography skilled artists were part of the crew on voyages of exploration. Matthew Flinders and the scientists on board the Investigator admired the precision of Bauer’s art greatly. Ferdinand Bauer was about forty years old, very hard-working and enthusiastic about his work.[18]

Flinders no doubt gave Bauer’s name to the cape in recognition of Bauer’s services to the British Empire, but more than one hundred years later a part of the Empire decided that the German name of this remote cape, bestowed by Matthew Flinders, was no longer suitable. The name was changed to Cape Wondoma. South Australia has honoured Flinders with the naming of the largest mountain range in the state (the Flinders Ranges), and with the naming of a university - the website of Flinders University reports that the famous navigator "is of particular importance to South Australia".[19] However, in 1916, with the increasing numbers of South Australians killed overseas in the war, there was no room for sympathy for Matthew Flinders’ gratitude to an Austrian member of his team.

Other German names of geographical features in remote coastal locations, and likely unknown to most South Australians, are the submerged oceanic rocks Berlin Rock and Krause Rock, whose names were also changed in 1918 (see the list of names changed in 1918).

♦ Notes:

1. Harmstorf, Ian. (1994). German Settlement in South Australia to 1914. In: Insights into South Australian History, vol. 2, South Australia’s German History and Heritage. Historical Society of South Australia Inc. pp.18-24

2. DEUTSCHLAND UEBER SUED AUSTRALIEN. (1916, May 27). The Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912 - 1954), p. 10. Retrieved November 10, 2023, from <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article59380115>

3. ARE WE IN AUSTRALIA OR GERMANY? A REMARKABLE MAP OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA. (1916, June 17). The Mirror of Australia (Sydney, NSW : 1915 - 1917), p. 3. Retrieved November 11, 2023, from <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article104645175>

4. DEUTSCHLAND UEBER SUED AUSTRALIEN. (1916, May 27). The Mail, p. 10.

5. DEUTSCHLAND UBER SUD AUSTRALIEN. (1916, June 3). The Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912 - 1954), p. 10. Retrieved November 10, 2023, from <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article59378090>

6. Moriarty, Richard. (2019, 16 January). A place by any other name: From Bismarck to Weeroopa to Brooklyn Park. News - State Library of South Australia. (Information Services Support Officer.) / see also PLACE NAMES IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA. (1925, August 1). Observer (Adelaide, SA : 1905 - 1931), p. 49. Retrieved August 7, 2021, from <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article165869698> Lecture by Mr Rodney Cockburn. The weekly luncheon of the Adelaide Rotary Club. Mr Cockburn had been a member of the Nomenclature Committee in 1916 and in this lecture in 1925 he spoke of some regrets about the place name changes in South Australia in World War I.

7. Harmstorf, Ian. (1994). A Trust Betrayed. In: Insights into South Australian History, vol. 2, South Australia’s German History and Heritage. Historical Society of South Australia Inc. p.58

8. Manning (2012), p.298

9. Manning (2012), p.356

10. Manning (2012), p.384

11. Manning (2012), p.470

12. Manning (2012), p.700

13. Manning (2012), p.762

14. Manning (2012), p.762

15. Appleton, R., & Appleton, B. (1993). The Cambridge Dictionary of Australian Places. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139084970. p.4

16. Hawes, James. (2018). The Shortest History of Germany. Exeter: Old Street Publishing (paperback edition). p.98

17. Gilbert, L. A. (1966). 'Bauer, Ferdinand Lukas (1760–1826)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, <https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bauer-ferdinand-lukas-1754/text1951>, published first in hardcopy 1966, accessed online 29 August 2023.

18. Lodewyckx, Prof. Dr. A. (1932). Die Deutschen in Australien. Stuttgart: Ausland und Heimat Verlagsaktiengesellschaft. pp.20-21

19. 'Matthew Flinders'. Website of Flinders University. <www.flinders.edu.au/about/history/matthew-flinders>. Accessed 09/11/2023.

♦ References:

Manning, Geoffrey H. (2012). A Compendium of the Place Names of South Australia. From Aaron Creek to Zion Hill. With 54 Complementary Appendices. Available online here.

Monteath, Peter (ed.). (2011). Germans: travellers, settlers and their descendants in South Australia. Kent Town (S.A.): Wakefield Press.

Nomenclature Committee's Report on Enemy Place Names. Parliamentary paper (South Australia. Parliament); no. 66 of 1916, pp. 1-4. Available at SA Memory, via State Library of South Australia, online here.