Victoria

Dr Heinrich (Henry) Backhaus, Bendigo

Part 1 - childhood in Paderborn; training for the priesthood; time in Sydney and Adelaide

Part 2 - life in Bendigo; his influence and active contribution to civic life; founding of the churches St. Kilians und St. Liborius

Part 3 - retirement and death; his legacy for Bendigo

In 1852 many South Australians left the colony to go to Victoria to look for gold, and the Catholic Church in SA nearly went broke. The Bishop could not afford to pay Heinrich Backhaus anymore and suggested to him that he go to Sydney. Backhaus decided that the Victorian goldfields were the place that needed his work most.[1]

Dr Backhaus' first chair in Bendigo

In the early days of the Bendigo goldfields, Backhaus, like the gold-diggers, lived in a very basic way in a tent, and he conducted church services in a tent (the altar took up most of the tent; the congregation stood outside the open entrance to the tent). Backhaus had only basic improvised furniture in his own tent, and his rough-hewn chair (cut from a log of wood) is preserved in a display case at the back of St Kilian’s church. His nephew, Theodor Mündelein, followed him from Paderborn to Australia, and after Backhaus’ death this rough old wooden chair passed into Theodor’s hands.[2]

Backhaus was described as “tall, spare and straight, rather austere-looking, with long auburn hair reaching to his square shoulders”. A Bendigo Advertiser journalist described him after his death as “a great disciplinarian, a firm upholder of law and order, and that he had a restraining influence on the diggers, who, understandably in the conditions of the time, tended sometimes to get out of hand”.[3] Backhaus had a reputation as a peace-maker, and though he spoke out strongly against the abuse of alcohol amongst the goldminers, he sympathised with the diggers when they were treated unfairly by authorities. Backhaus made friends easily and was a vigorous preacher who spoke English well though with a strong German accent.

Dr Backhaus, "the best-known name in early Bendigo"[4], was a well-known public figure: he often attended and spoke at public meetings, and he was respected at land sales as a shrewd bargainer and land speculator and he often wrote articles in the local newspapers. He had a big reputation as a healer of the sick. It appears he may have picked up some knowledge of Indian herbalism while he was in India. At any rate, many people sought him out when they were sick.[5]

Backhaus was particularly interested in medicine and in helping the sick, and he was a driving force in the establishment of Bendigo’s first public hospital, which opened in November 1853. He was on its Board of Directors. He also participated actively in meetings that planned a library (“Mechanics’ Institute”) for Bendigo and also the Town Hall building.[6]

He recognised the potential of the Bendigo area for wine-growing and encouraged his fellow Germans to plant vines and make wine. The early wine-makers of Bendigo include Carl Heine, Georg and Albert Bruhn, Carl Pohl, Frederick Grosse, Wilhelm Greiffenhagen, Johann Kahland and August Fischer. Fischer’s ‘Shamrock Vineyard’ was on land leased from Dr Backhaus.[7]

A bust of Dr Backhaus in the Chancery office of the diocese in Bendigo

Backhaus played a part in lobbying for an effective water supply for the growing city and for the establishment of a fire brigade. He lobbied also for the building of a railway from Melbourne to Bendigo and was an official speaker at a banquet for the opening of the line in October 1862.[8]

It is not clear where Dr Backhaus gained his business acumen, his interest and skill in finance and real estate.[9] He bought land in the growing city of Bendigo at valuable locations, such as corner blocks in the centre of the town.[10]

Backhaus was extraordinarily careful and frugal about money, never wasted it or spent money unnecessarily, but he was also generous to the poor people of Bendigo and did this in modest and unostentatious ways. The people knew that he was wealthy; he made no secret of it and told them so. However, he told the people of the parish that the was developing his wealth for the future benefit of the parish, that his wealth would benefit the advancement of religion in the parish and help the provision of charity for the people of the district.[11]

Shortly before the end of Backhaus’ life the writer John Neill Macartney published a book entitled Sandhurst : as it was and as it is (Bendigo’s official name was Sandhurst for a period of about 40 years up to 1891). In this book Macartney described important personalities and places and industries in Bendigo, which he described as having become “a stately city”. He wrote that Dr Backhaus “is a very Midas in respect of wealth”.[12] (King Midas is a figure from ancient Greek and Roman myths. In one story anything that Midas touched turned into gold.)

In 1993 two writers described Backhaus' prominence in Bendigo as follows:[13]

He was a forerunner in all progress concerning Bendigo, the laying out of the streets, its water supply, the hospital, the railway, the fire brigade and so on. (…) While of an independent mind, he was affable and could converse with people of all classes and religions.

Annette Marie O'Donohue & Bev Hanson

Sign at St Kilian's Primary School, Bendigo - the Backhaus Building of the school is also visible

Backhaus’ first church in Bendigo was a primitive building made of wooden slabs and canvas. Later a substantial church of stone was built and named after St Kilian (the saint depicted above the 'Paradiesportal' entrance to Paderborn Cathedral in Backhaus’ hometown). Dr Backhaus bought and gifted to this new church an impressive pipe organ that he commissioned from a master organ builder in his hometown of Paderborn in Germany. R. A. (August) Randebrock built this organ in 1871 and it was shipped to Australia and installed in St Kilian’s church by George Fincham, an English organ builder who had emigrated to Australia and was based in Richmond in Melbourne.[14]

In 1887 the original stone church was declared unsafe; the foundations of the church had become unstable due to subsidence in the land as a result of mining in the area, and the church was demolished. A new church, the current St Kilian’s, was designed by Bendigo’s famous German architect W C Vahland, and was built of wood, a lighter construction (of oregon and hardwood), and was opened in July 1888. Dr Backhaus was no longer alive to see the new church, which is beautiful in its simplicity and for the the quality of its wooden furnishings and fittings, such as the attractive series of timber arches. It is probably the largest wooden church in Australia. The Randebrock organ was transferred into the new wooden church by George Fincham.

St Kilian's Church, Bendigo

Plaque commemorating the visit by the Archbishop of Paderborn to St Kilian's Church, Bendigo in 1988

The wooden interior of St Kilian's Church, Bendigo

The Randebrock organ in St Kilian's Church, Bendigo

John Stiller of the Organ Historical Trust of Australia described the organ in detail in 1979 before the organ was restored in 1981-82, and he included these comments: “The organ in St Kilian's, Bendigo, is the only large nineteenth century German organ in Australia. (…) Due to the effects of wars and the continual striving towards "modernisation" and "improvement", such instruments have become extremely rare in Germany. The fact that this organ deviates but slightly from its original form makes it an instrument of international historic importance.”[15]

The Victorian Heritage Database says of this organ: “The oak casework, in the Gothic style, is elaborately carved and highlighted with colour. This is one of Australia's most notable organs because of its rarity. The German origin and character of the instrument make it quite different from other English style pipe organs which were built in, or exported to, Australia.”[16]

Statue of a saint on the case of the Randebrock organ in St Kilian's Church, Bendigo

A statue of St Liborius (rather than St Kilian[17]) at the centre of the organ’s case carries a white scroll – on that scroll are the name of the organ builder and the year (1871) and place of construction (Paderborn).

The stop knobs of the Randebrock organ in St Kilian's Church are labelled in German and in English

The stop knobs above the console of the organ are labelled in both German and English, for example "8 Fuß Fernflöte" / "Distant Flute 8 feet".

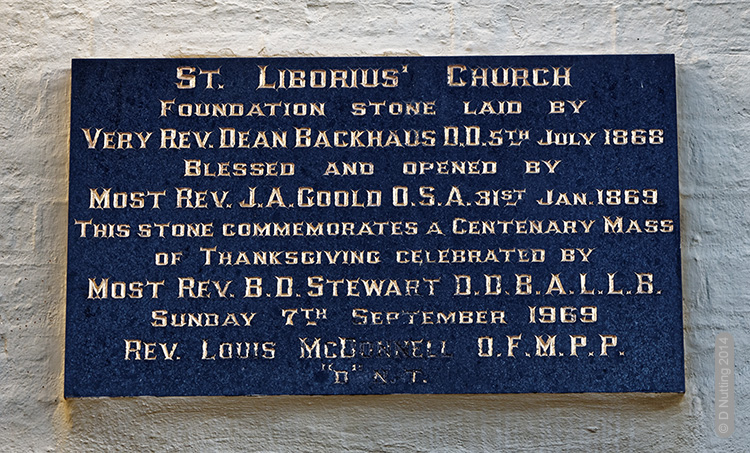

Apart from St Kilian’s in central Bendigo, Dr Backhaus also established a church at nearby Eaglehawk, and dedicated it to St Liborius, the other patron saint of his German hometown (Paderborn). The church was designed by Bendigo’s well-known German firm of architects, Vahland & Getzschmann, and was completed in 1869. A plaque shows that the foundation stone was laid by Dr Backhaus.

The St Liborius Church at Eaglehawk, near Bendigo

A plaque at the St Liborius Church at Eaglehawk, near Bendigo

♦ Notes:

1. Hussey (1982), pp.53-55

2. Hussey (1982), pp. 71, 168

3. Hussey (1982), p.92

4. Hussey (1982), front flap text

5. Hussey (1982), pp.93-98

6. Hussey (1982), pp.123-125

7. Hussey (1982), p.125

8. Hussey (1982), p.126

9. Hussey (1982), p.173

10. Sherborne, Craig. (2002). "Investor priest’s bequest lives on". Herald Sun, Monday 26th August 2002, edition #1, p.7

11. Hussey (1982), p.176

12. Macartney, John Neill. & White, E.J. (1882). Sandhurst : as it was and as it is. Sandhurst : Burrows and Co, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-485234974>, p.122

13. O'Donohue, Annette Marie. & Hanson, Bev. (1993). Where they lie : early burials on the Bendigo Goldfields, 1852-1870. Maiden Gully [Vic.] : A. O'Donohue. p.36

14. Organ Historical Trust of Australia. (n.d.) St Kilian's Catholic Church, Bendigo. Available at: <https://www.ohta.org.au/organs/organs/StKilians.html>

15. Stiller, John. (1980). St Kilian's Roman Catholic Church, Bendigo. Organ Historical Trust of Australia. Available online at: <https://www.ohta.org.au/doc/js_bendig/0.htm>

16. St Kilian's Catholic Church & Organ. Victorian Heritage Database. Property No B3508. Available at: <https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/70121>

17. Maidmente, John. Cited in: Organ Historical Trust of Australia. (n.d.) St Kilian's Catholic Church, Bendigo. Available at: <https://www.ohta.org.au/organs/organs/StKilians.html>

♦ References:

Cusack, Frank (editor). (1998). Bendigo - the German Chapter. Bendigo (Victoria): The German Heritage Society. pp.113-116

Hetherington, John. (1966). Pillars of the Faith. Churchmen and Their Churches in Early Victoria. Melbourne: Cheshire.

Hussey, John. (1982). Henry Backhaus, Doctor of Divinity, pioneer priest of Bendigo / John Hussey. Bendigo [Vic.] : St. Kilian's Press

Owens, A. E. 'Backhaus, George Henry (1811–1882)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/backhaus-george-henry-43/text4199, published first in hardcopy 1969, accessed online 29 December 2023.