Spiritual leaders

Clamor Schürmann

Training

The Protestant St Bartholomew's Church in Altenburg, Thuringia, Germany. Schürmann and Teichelmann were ordained as Lutheran priests in 1838 in this church, the oldest parts of which date back to the 1100s.

Photo source: J.-H. Janßen, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Clamor Wilhelm Schürmann (1815-1893) was a Lutheran missionary and pastor, born on 7 June 1815 in Schledehausen, near Osnabrück, Kingdom of Hanover. His parents died when he was a child. After his elementary education he entered Johannes Jänicke's Missionsschule in Berlin to train as a missionary. At the Missionsschule he got to know a fellow trainee called Christian Gottlob Teichelmann (1807-1888). The students there studied Latin, English, Greek and Hebrew as well as foreign geography, world history, Church history and theology.

Pastor A. L. C. Kavel and George Fife Angas contacted the Evangelical Lutheran Mission Society of Dresden hoping to recruit missionaries for the new colony of South Australia. In 1836 Schürmann and Teichelmann began further missionary training at Dresden, and in February 1838 the Society ordained them as Lutheran pastors. They arrived in Adelaide in October in the ship Pestonjee Bomanjee, which also carried the new governor of the colony of South Australia, Governor Gawler.[1]

South Australia

With little financial support, Schürmann and Teichelmann established the first school for Aborigines in South Australia. They started teaching in the open air, then moved to Piltawodli (possum house), an Aboriginal reserve established on the northern bank of the River Torrens in Adelaide. For German missionaries learning the local indigenous language was the starting point of their missionary work[2] (for many British missionaries engaging with the local language was not so important). Teichelmann and Schürmann published a grammar book in 1840 with around 2000 words of the Kaurna language, which is now a crucial resource for the present-day linguists and other people who are trying to revitalise the Kaurna language. Governor Gawler praised the work of the two German missionaries, and described them as 'serious, intelligent, persevering Christian men'.

Malcolm King wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald in 2008 about the significance of the work of Schürmann and Teichelmann for the revival of the Kaurna language:[3]

The pair were not cane-wielding Bible-bashers who sought to eradicate the local language. They were Christian linguists who meticulously recorded the Kaurna language knowing that it faced extinction. They saved more than they knew.

Malcolm King

Teichelmann was a dedicated and outspoken advocate for the Aboriginal people of Adelaide. He became a government interpreter, and worked a farm as well as serving as pastor to a Lutheran congregation in Adelaide. He married Margaret Nicholson on Christmas Day 1843 and stayed active in church life until his death in 1888.[4]

Schürmann became Deputy-Protector of Aborigines at Port Lincoln in 1840. He often worked as an interpreter during police investigations and travelled to Adelaide for court proceedings. By the end of 1840, he had collected 500 words of the Parnkalla (Banggarla) language. Schürmann repeatedly asked for government support for an agricultural settlement and school for Aborigines. In 1844, he published a Parnkalla dictionary. Schürmann faced many challenges in the Port Lincoln area. There was frequent violence between Aboriginal people and British settlers. Attacks by inland Aboriginal groups, who retreated from the edges of the settled areas after carrying out an attack, led to harsh, indiscriminate retaliation by the English authorities. Schürmann was caught in the middle. He was supposed to communicate with the Aboriginal people, but his advice on guilt and innocence was ignored by the colonial authorities, who preferred to carry out quick executions. This made it more difficult for Schürmann to build trust with the Barngarla and Nawu people.[5]

In 1847 Schürmann moved to Encounter Bay, married Wilhelmine Charlotte Maschmedt (like Schürmann she was originally from Osnabrück), and they eventually had nine children. After the Encounter Bay mission failed, he returned to Port Lincoln in 1848 as an interpreter and opened a school in 1850 with lessons conducted in the Parnkalla language. The school closed in 1852, and the pupils were moved to the Native Training Institution at Poonindie established by English church authorities, but there was no learning or teaching in indigenous languages. In 1853 Schürmann was invited to become pastor to a German-speaking community of Lutherans in south-western Victoria, an offer which he accepted.

The language legacy

The meticulous records and descriptions kept by Schürmann and Teichelmann of Indigenous cultural practices, and above all of the language used by the original inhabitants of South Australia, are highly valued by Indigenous South Australians who are trying to revitalise the everyday use of those languages.

In 2012 the Parnkalla (also spelled Barngarla) people of South Australia's Eyre Peninsula began the long journey to revive their language with the help of the dictionary written by Schurmann in 1844. It is the source for over 2,500 words which are being worked back into the local vocabulary. Lynley Wallis of Flinders University told ABC News in 2015: "Clamor Schurmann could have conversations with Aboriginal people that just weren't possible for early settlers. He was able to interact with Aboriginal people on their terms. It was a two-way exchange of cultural ideas; there was a lot of trust involved in that."[6] Schürmann identified and described in great detail many key cultural features and customs of the Parnkalla people, including a particular set of initiation ceremonies.[7]

One reason that Schürmann was able to establish such good relationships with the Indigenous people of the Adelaide area and in the Port Lincoln area was that he genuinely saw the Indigenous people as equal human beings at a time when any other Europeans viewed them as lesser creatures. This is also reflected in the large number of personal Aboriginal names he used in his letters and reports. Many Europeans imposed made-up names or English names on Aboriginal people, but Schürmann identified them by their own names, a sign of his respect for them.[8]

The Dresden missionaries accomplished by far the most comprehensive and best documentation of the (Kaurna) language as it was spoken in the nineteenth century.[9] "Schürmann has left a record that continues to offer valuable data to linguists, anthropologists and historians, and be of ongoing relevance to the descendants of the people with whom he worked."[10]

Western Victoria

Schürmann gravestone, South Hamilton cemetery

Text includes: born in 1815 near Osnabrück (Germany); died 1893 in Bethanien (Bethany) in S.A.

The Church of England in South Australia offered Schürmann the opportunity to become a priest (minister) in the Anglican Church, however he rejected that and in 1853 accepted the invitation to become the Lutheran parish priest of a community of Germans in south-western Victoria, most of whom had moved there from the Barossa region in South Australia. Schürmann helped them to gain access to land near Hamilton (which was known as 'The Grange' at that time) by conducting negotiations with the Victorian authorities. These Germans named their village Hochkirch after a small town in Saxony in eastern Germany. As was common for the pastors in German communities in Australia, Schürmann was for a time also the teacher in the Hochkirch school, and he became a highly respected and influential member of the community. For around 40 years he served Lutherans in a wide geographical area, and by 1860 Schürmann was travelling large distances each year in order to run occasional church services for Lutherans in places as far afield as Mount Gambier (in South Australia), in Mortlake, in Warrnambool, and as far east as Waldkirch (Freshwater Creek) and Germantown (Grovedale) in the Geelong area. On the way to each of these places he would minister to isolated German families along the route. When German farmers started to move north from the Western District into the Wimmera, he travelled to visit them at places like Natimuk, Vectis and Green Lake until they were able to have a pastor of their own in the mid-1870s.[11]

One visitor to Hochkirch who enjoyed meeting Pastor Schürmann was the 'vagabond'. "The Vagabond" was the pen name of John Stanley James, an Englishman who moved to Australia at the age of 31. In 1884 he started writing a series of articles for the Melbourne newspaper The Argus, entitled 'Picturesque Victoria', about places he visited during a tour around the colony.[12] He was impressed by the quiet, patient and hard-working population of Hochkirch, and in his opinion Pastor Schürmann "rules the settlement as despotically as any Irish priest could his parish." However, he felt that Pastor Schürmann was a wise man and he was struck by the range of books in Schürmann's study - "The table of his study is strewn with English and German books by good authors." 'The Vagabond' wrote furthermore that: "In his 70th year, his white hair is still luxuriant, his face ruddy as a pippin, and he is still active in body and mind."[13] ('face ruddy as a pippin' = an old-fashioned expression saying that someone's face is reddish due to good health and perhaps round - a pippin is a type of apple)

'The Vagabond' wrote of Schürmann's community:[13]

A number of quiet, saving Prussians have been established here for many years. Soon we get into the district of their farms. Here by the roadside are the signs of German bootmakers and tailors. There is a flavour of Vaterland around everything. (...) Take away the eucalyptus and we might be in Deutschland. (...) The men and the women we see are stolid and patient, (...) the children are sturdy and flaxen-haired. Hochkirch is essentially a peaceful and sober place.

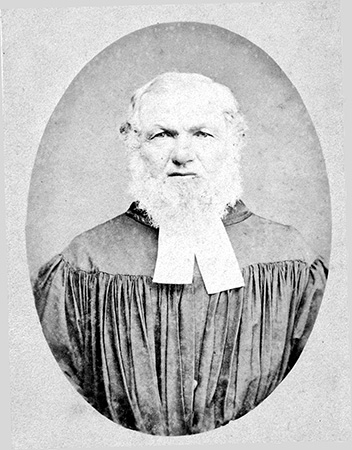

Pastor C W Schürmann

Photo source: St Michael's Lutheran Archives, Tarrington

Heide Kneebone, writing in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, concluded that Schürmann "was a gifted linguist and a compassionate and dedicated missionary, and his documentation of the indigenous languages in the Adelaide and Port Lincoln areas was an enduring legacy. Predeceased by his wife in 1891, Schürmann died on 3 March 1893 while attending synod at Bethany, South Australia; he was buried in West Terrace cemetery, Adelaide, and later reinterred in South Hamilton cemetery. Four sons survived him."[14]

In the Tarrington area and in Minyip and Natimuk in the Wimmera there are country roads and streets that carry the name Schürmann, as a result of sons and grandsons of Pastor Schürmann living in those places.[15]

♦ Notes:

1. Kneebone (2005).

2. Leitner, Gerhard (2006). Die Aborigines Australiens. München : C.H. Beck. p.101 / McCaul (2017), p.60

3. King, Malcolm. (2008, September 6). The resurrection of a language long lost. The Sydney Morning Herald. Online <www.smh.com.au/national/the-resurrection-of-a-language-long-lost-20080905-4aqi.html>. Accessed 08/08/2024.

4. Kneebone (2005).

5. McCaul (2017), p.61

6. Dulaney, Michael & Williams, Deane. (2015, Nov 16). Links to German linguist hold key to reviving an Aboriginal language. ABC Eyre Peninsula. Available online here.

7. McCaul (2017), p.63

8. McCaul (2017), p.60

9. Amery (2013), p.43

10. McCaul (2017), p.74

11. Huf (2003), p.274

12. Barnes, John. 'James, John Stanley (1843–1896)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/james-john-stanley-3848/text6113, published first in hardcopy 1972, accessed online 11 August 2024.

13. PICTURESQUE VICTORIA. (1885, April 11). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), p. 4. Retrieved August 10, 2024, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article6074626.

14. Kneebone (2005)

15. Huf, Betty. Personal communication (email). 21/10/2025. (Local historian)

♦ References:

Amery, Rob. (2013). Beyond Their Expectations: Teichelmann and Schürmann’s efforts to preserve the Kaurna language continue to bear fruit. In: Beyond All Expectations - The Works of Lutheran Missionaries from Dresden, Germany amongst the Aborigines of South Australia, 1838-1853. Adelaide: Kaurna Warra Pintyanthi (KWP) - The Kaurna Language Reclamation Program, Discipline of Linguistics, School of Humanities, University of Adelaide. August 2014 (Second Edition). Available online here.

Huf, Betty (2001, January). Personal communication. (Local historian).

Huf, Betty. (2003). Courage, patience and persistence : 150 Years of German settlement in Western Victoria. Tarrington, Vic. : Sesquicentenary Committee, St Michael's Lutheran Church.

Kneebone, Heide. 'Schürmann, Clamor Wilhelm (1815–1893)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/schurmann-clamor-wilhelm-13284/text23925, published first in hardcopy 2005, accessed online 25 June 2024.

Leske, Everard. (1996). For Faith and Freedom: the Story of Lutherans and Lutheranism in Australia 1838-1996. Adelaide: Openbook Publishers. pp.67-68, 136

Lockwood, Christine. (2014). Dresden Lutheran Mission work among the Aboriginal people of South Australia 1838–1853. In: Beyond All Expectations - The Works of Lutheran Missionaries from Dresden, Germany amongst the Aborigines of South Australia, 1838-1853. Adelaide: Kaurna Warra Pintyanthi (KWP) - The Kaurna Language Reclamation Program, Discipline of Linguistics, School of Humanities, University of Adelaide. August 2014 (Second Edition). Available online here.

Lodewyckx, Prof. Dr. A. (1932). Die Deutschen in Australien. Stuttgart: Ausland und Heimat Verlagsaktiengesellschaft. p.55

McCaul, Kim. (2017). Clamor Schürmann’s contribution to the ethnographic record for Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. In: German ethnography in Australia. (editors: Peterson, Nicolas and Kenny, Anna). Canberra: Australian National University Press. pp. 57-77