First World War

The Effects of the First World War on Australia's German-speakers

Pre-war

Armed conflict between a German kingdom or state and the United Kingdom would have seemed illogical to many people in the British Empire for most of the 19th century. Throughout that century there were long-standing ties between Great Britain and some of the German states (and later on, the German Empire) at the highest levels of society. In 1714 Britain got itself its next king from Germany – George the 1st became king of Britain as well as being the ruler of the electorate of Hanover, and he couldn’t speak much English. Up until 1837 Britain’s king was also the ruler of Hanover in the German-speaking lands. Queen Victoria confirmed this connection with the German states by marrying Prince Albert of Sachse-Coburg-Gotha, who in the course of time became popular with Britons and with the people of British colonies like Australia.[1]

German national pride in Australia

When Prussia defeated France in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, many different kingdoms, principalities and states of the German-speaking lands came together and formed the German Empire (see the page about Otto von Bismarck). Many German-Australians and Germans living in Australia felt some pride in the new united Germany. Germans living in Australia even sent gifts to Bismarck, the Empire’s Chancellor.[2]

Before the war, German Australians were highly respected.[3] Between 1839 and 1914, they made a significant contribution to the development of Australia, particularly in South Australia (in 1900, almost 10% of the South Australian population was German Australian).

Rev. John Blacket, a Methodist minister and historian, published a history of South Australia in 1911 (only three years before World War One), and he devoted much of chapter 8 to "the coming of the Germans" and described the German immigration as one of "the most important events in the early history of South Australia".[4] He wrote: "There must be something in men and women who will sacrifice home and fatherland for conscience sake. These German refugees were the ‘pick of Silesia’. Splendid colonists they made - devout, sober, contented, industrious.”[5]

In the last few years of the 19th century British and Australian attitudes to Germany became more tense and distrustful when Kaiser Wilhelm II started to take Germany’s international politics and diplomacy more and more into his own hands[6]. Germany expanded its trade and colonies, partly in an attempt to “catch up to” Britain and France in these fields.[7] Germany gave practical support to the rebels who challenged Britain in the Boer War.[8] German imperialism in the western Pacific Ocean became a worrying development. When Germany annexed north-east New Guinea, it became the nearest major power to Australia’s shores. This worried the government of Queensland particularly. Anti-German feelings started to increase in Australia.[9]

War broke out

Many German Australians were in the Australian army and fought and died for Australia. On the war memorial in the public gardens of Tanunda (Barossa Valley) are the names of eight soldiers who fell in the war. Six of them are German names.

The war caused much misery for Australian families as reports of deaths at the front arrived in Australia, and propaganda by the federal government stirred up anti-German feelings in the community and in the newspapers. In Australia during the First World War military service was voluntary, and the government did its best to portray Germany and Germans as beastly and awful, in order to increase the numbers of soldiers who volunteered. "All things German fell into disfavour".[10]

The great majority of German-Australians and Australians of German descent were loyal to Australia and the British Empire, but many still felt affection for the German language (especially for the role it played in services in Lutheran churches) and for German cultural traditions that they had grown up with; they drew a distinction between politics and culture – for Germans, calling Australia ‘Home’ was not a denial of their cultural heritage.[11] This was a distinction that some British-Australians could not understand.

The First World War was a blow to the status of the German language in Australia. Not only in Australia, but also internationally German had been a significant language, especially in the various fields of science. In 1909, Max Planck – who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1918 – gave a series of physics lectures in German at Columbia University in New York. German also played an important role in Asia: in 1907, a medical university was opened in Shanghai where German was the language of instruction.[12]

Early in the war the Australian federal government banned the importation of books and other printed resources produced in Germany, and in late 1917 it prohibited the publication of German-language papers and magazines in Australia.[13] The use of spoken German in church and community life was regularly criticised in letters to newspapers and in the various parliaments of Australia.[14] Der Lutherische Kirchenbote (English: Church Messenger) für Australien was the official church newspaper of the Evangelical Lutheran Synod in Australia, which published important news, reports and information for the Lutheran community in Australia in German. It was published by Oscar Mueller in Hochkirch, Victoria. This German-language newspaper was suspended in 1917.

The picture shows the masthead of the last edition (20/12/1917) of the Lutherische Kirchenbote, before the government suspended its publication.

In isolated country communities of German-descended people in South Australia where English families were few, and where there was no British-Australian policeman, German would be spoken in the street and called across the road, such as in Springton in the Eden Valley. However, people avoided speaking German wherever possible in Adelaide.[15]

The Bryce Report

The Bryce Report of 1915 made the anti-German atmosphere in Australia even worse. This Report was a propaganda publication of the British government that claimed to document atrocities committed by German troops in Belgium. However, the 'evidence' on which James Bryce’s committee based its allegations “was, in many cases, extremely flimsy”, according to the UK National Archives.[16] This British publication was promoted in Australia and increased the level of hatred that German-Australians experienced. You can read more about the Bryce Report and its effect in Australia here.

John Molony, Professor of Australian History at the Australian National University, wrote in 1987:[17]

Patriotism in many guises gripped scoundrels and the decent alike. Anyone or anything to do with Germany, whether person, place or product, suffered discrimination or internment, name change or rejection.

Professor John Molony

Examples of the effects of the wartime atmosphere

In 1914 most white Australians identified with "Mother England". In her book The Anzacs the Australian author Patsy Adam-Smith wrote:[18]

"The people didn't know what to do", my father answered when, as a child, I questioned him about the ill-treatment of a German in his town. "We hadn't had a war before this."

Patsy Adam-Smith

Read more here about most Australians' feelings towards Great Britain in the early years of the 20th century.

Some German Australians were interned whose families had lived in Australia for three generations. Employment became difficult for German-Australians, and as a result some went into internment camps voluntarily.[19] Some British Australians no longer wanted to work together with "Germans" and it became harder for German Australians to find work.[20] Hermann Homburg, the Attorney General of South Australia, had to resign from his position. He was born in South Australia and had never been out of South Australia.

In Mentone, a bayside suburb of Melbourne, a group of young local men went to a house near the pier in Naples Road and smashed rocks through its fragile walls, targeting a long-time local German immigrant, Oscar Wetzel. His only “offence” was using a telescope to observe the bay — and permitting others to glance through it for a penny — yet neighbours accused him of spying on ship movements. Those ready to believe the accusation allowed the harassment to escalate until Wetzel, fearing for his safety, asked to be interned.[21]

The mayor of Rainbow in Victoria's Mallee region had to resign because he was German Australian. This happened to mayors and councillors elsewhere also. At Katoomba Council in New South Wales Johannes Berghoefer and Charles Lindemann were forced to resign from their positions. They had come to Australia as young men and both had played an active part in the development of the Blue Mountains region.[22]

The Australian military authorities were worried about German missionaries who worked in remote areas of the country. The authorities spied on the German Catholic missionaries (the Pallottine Fathers) who worked with Indigenous Australians at the Beagle Bay (Ngariun Burr) mission on the Dampier Peninsula in the Kimberley region. After war broke out navy patrol boats visited the mission and searched for a radio transmitter but found nothing. The government thought that the missionaries, who had lots of cattle, might give supplies of meat to German ships that operated in the Indian Ocean. The German missionaries were not allowed to leave the mission for the rest of the war. During that time of forced isolation they and their Aboriginal helpers built by hand a beautiful church, the Sacred Heart Church, which is famous for its mother-of-pearl shell altar.[23] The Sydney Morning Herald: “Sacred Heart is an incredible marriage of German and Aboriginal culture.”[24] (Many of the Aboriginal children from the Kimberley region whom the mission educated and prepared for employment lost contact with their parents and became part of the Stolen Generation. The mission was closed by 1976 and since then the Beagle Bay Aboriginal Community has been self-governing.)

The altar of the Sacred Heart Church at Beagle Bay, W.A. It includes tribal symbols of the local Indigenous Australians and Christian symbolism, inlaid on the altar using mother-of-pearl.

Photo appears here by kind permission of outbackjoe.com

German schools had to close. The German language was forbidden in government schools. The Premier of South Australia said that the Education Department must not employ anyone of German background or who had a German name. Most people had a negative attitude towards the German language, however, the Education Minister in New South Wales, Arthur Griffith, said on the 29th June 1915 in the NSW parliament:

I might remark that we are at war with the German nation; we are not at war with German literature.

In South Australia all 49 Lutheran schools were closed in 1917. After the winter break many of these were re-opened as state schools in the same buildings (rented by the Government from the congregations), with new teachers. This sudden change was traumatic for the youngest children particularly, as they couldn't understand why the Government would want to do it. From then on the students had no more German and Religion lessons.

Some British-Australians’ anger towards anything that seemed to have a German connection even affected church buildings. Arson attacks completely destroyed by fire Lutheran churches at Edithburgh (in the south-east corner of Yorke Peninsula, S.A.), Murtoa (about 300 kilometres north-west of Melbourne) and Netherby (a village about 400 kilometres north-west of Melbourne). An unknown person painted the doors of the Lutheran church at Quorn (about 40 kilometres northeast of Port Augusta in South Australia) red, white and black (the German imperial colours) because the pastor conducted services in the German language.[25]

Many Australians believed all propaganda lies about German Australia. Some German Australians were put into internment camps simply because an Australian (perhaps even a business rival) had said that the German Australian had said something negative about England, even if this was just a rumour spread by a neighbour.[26]

The nationalist fervour of the time helped to increase the sales of Australian lager beer, as fewer imported German beers were sold, which had enjoyed a good reputation up until then. Read more here about the reputation of German beers before the First World War. The Australian Brewer’s Journal wrote:

The Teutonic brands which have been exported here by the enemy are taboo. Our lagers are equal if not better than their fancy brands.

At the start of the war St Kilda Football Club (Australian Rules Football), playing in the Victorian Football League, wore team colours that were the same as the colours of the flag of the German Empire (red, white and black). At a match played in Geelong between St Kilda FC and Geelong FC in 1914, many uncomplimentary remarks about St Kilda’s colours were heard. At St Kilda’s annual meeting on Monday 14th December 1914 the club decided to change its colours to the colours of the Belgian flag (black, red and yellow – incidentally they are the colours of the present-day German flag).

The Secretary of the club, Mr George Inskip, explained to the members at this annual meeting that nearly every football club in Melbourne had colors of one or other of the various German States. He believed the football club was established long before the German Empire was constituted. (In fact, the club was founded in 1873, two years after the foundation of the German Empire.) According to a journalist the chairman of the meeting then said: “Germany copied our colors”, and the members responded with laughter.[27]

Not all fans approved of the change of colours. One life-long fan of St Kilda wrote to Melbourne’s sporting newspaper The Winner and said he was shocked by the change of colours. He wrote: “I don't think the fact of St. Kilda's changing its colors will affect the course of the war.” St. Kilda reverted to the original colours in 1922.[28]

The Ferntree Gully Shire Council (east of Melbourne) held its monthly meeting on Saturday October 7th 1916. The Council received a letter from the Upwey Progress Association asking for a street lamp to be replaced with a new one because it had the words "Made in Germany" on it. The Council informed the Upwey Progress Association that this lamp was purchased before the war, and that the Council had no money at present with which to replace it.[29]

Matilda Rockstroh, who worked in the post office within the St Kilda railway station in Melbourne, Australian-born and in the public service for 37 years, with no evidence of any disloyalty, was moved out of her position because of her background. She was no longer allowed to have contact with customers.[30]

Edmund Resch at the start of his internment in 1917.

Photo: National Archives of Australia. NAA: D3597, 5498

Edmund Resch, the founder of Resch's Beer in Sydney, was interned. Resch had emigrated to Australia in 1863 at the age of 16, and was naturalised in 1889. His two Australian-born sons were in charge of running the brewery when the war broke out. Nevertheless, Edmund Resch was 71 years old when he was arrested in 1917 and interned at Holsworthy until the end of the war. A photo was taken of him at the start of his internment, holding his official number. He had lived in Australia for 54 years and you can assume that the internment procedures were humiliating for this elderly, dignified-looking man.[31]

Gustav Weindorfer had some men carry to his chalet near Cradle Mountain (Tasmania) what someone claimed was wireless equipment. It turned out to be a new stove. Someone claimed that a clothesline at Cradle Mountain was an aerial.[32]

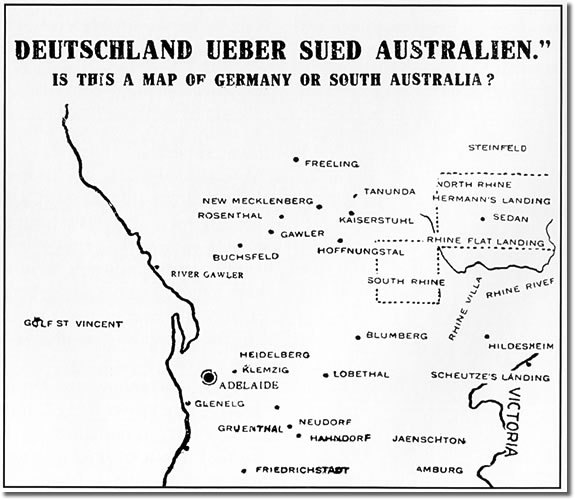

Governments in Australia changed very many German place names, despite the fact that these German names derived from "pioneers". In South Australia the government changed 69 names of places and geographic features. See a List of German place names in South Australia.

It is interesting to note that Adelaide, the name of the capital of South Australia, was originally German. Read about the name Adelheid. The government in South Australia did not change this place name of German origin.

Place name sign in Cambrai, a village located east of Eden Valley and 9 km south of Sedan in South Australia. The original name of the place was Rhine Villa. The new name Cambrai referred to a battle in France in 1917 during the First World War.

Many German Australians changed their name. Paul Schubert, teacher at Sturt Primary School in Adelaide, had to change his name in order to keep his job. He became Paul Stuart in 1916.[33]

Even the British royal family needed to change its name. Through the marriage of Queen Victoria (1819-1901) to a German prince in 1840 the British royal family had received a German surname. In 1917 King George V. changed the family name. No longer Saxe-Coburg-Gotha; the new family name was Windsor. Victoria's cousin changed his family name from Battenberg to Mountbatten. Mountbatten sounded more English.[34]

Map: The Mirror of Australia, 17th June 1916, page 3

These prejudices did not exist only in Australia. In the USA 'sauerkraut' received the new name 'liberty cabbage' and 'hamburgers' received the new name 'salisbury steaks' (named after the doctor Dr. J.H. Salisbury: he recommended eating a burger three times daily). Sometimes these new names did not last.

An amendment to the "Aliens Restriction Order" on 28th July 1915 prohibited enemy aliens and naturalised subjects from changing their name or their business name.

Anti-German hysteria outlasted even victory. In Hobart Charles Metz, a butcher who was born in Australia, was beaten by a crowd and his shop was looted when he failed to fly an Australian flag after the Armistice. People who stood up for him pointed out that if Metz’s grandfather had been born in Germany, so had the King’s grandfather (i.e. Prince Albert, the German husband of Queen Victoria).[35]

As late as 1927 some residents of the Brighton area near Melbourne expressed strong criticism of the local council when it bought three pianos from Germany for the Town Hall and for another hall owned by the council.[36]

The armed forces of most countries involved in the war were based on conscription (compulsory military service). Australia did not have conscription, and this was a controversial matter – many Australians wanted conscription to be introduced, and many Australians were against conscription. During the war the Australian Government tried to introduce conscription. During two referendum campaigns nationalistic and anti-German propaganda was rampant in the Prime Minister Billy Hughes’ push for conscription.[37] Australians rejected conscription in the first Conscription Referendum in October 1916. "Patriots" blamed the failure of this referendum on Roman Catholics and German Australians. These "patriots" were sure that German-Australians had voted against conscription and that the large numbers of German-Australians must have affected the vote.

A bronze bust of Prime Minister Billy Hughes in Prime Ministers Avenue, Ballarat Botanical Gardens, Victoria.

At a public meeting at Tamworth in New South Wales (Saturday 1st December 1917) before the second referendum the Prime Minister Billy Hughes blamed the failure of the first conscription referendum on three groups in Australian society, including German Australians.[38] Before the second referendum his government disenfranchised (= took away the right to vote) anyone whose father was born in an enemy country (even if that person was born in Australia).[39] Billy Hughes had Welsh parents and came to Australia at the age of 22. James Catts was a union secretary, politician and businessman who led the New South Wales no-conscription campaign. In an article in the newspaper The Australian Worker in December 1917 he said that the future of young Australians should not be decided by “imported jingoes” (he meant Billy Hughes). He wrote:

For political reasons, Australian-born citizens whose fathers' birthplace is enemy soil — numbering 100,000 — HAVE BEEN DISFRANCHISED by our Welsh Kaiser.

James Catts[40]

(The newspaper, or Mr Catts, misspelled the word 'disenfranchised'.) This denial of the right to vote, this sign of doubt at their loyalty, angered men fighting in the AIF (Australian Imperial Force) whose parents were German-Australians. Read one soldier's complaint about this. John Fihelly was a Queensland government minister who campaigned against conscription, and he wrote in Brisbane’s Daily Standard newspaper in December 1917 that the Federal government clearly thought Australians of German descent were good enough to fight (in the Australian Army) but those same German Australians were apparently not good enough to vote in the conscription referendum.[41] The second Conscription Referendum, held in December 1917, was also defeated.[42]

In The Australian People and the Great War, Michael McKernan wrote that up until 1914 the German-Australians "had been admired and respected. But the Australians, so heavily committed to the war emotionally, needed to manufacture a war close at hand lest their knitting and their fund-raising be their only real war experience. The German-Australians became the scapegoats for Australia's fanatical, innocent embrace of war."[43]

After the war, a difficult problem arose with the nearly 7,000 people held in internment camps in Australia who had been born in Germany or were of German background. As soon as ships were available, about 5,200 of them were deported to Germany. This included some people who had arrived from Germany as babies and who had later become Australian/British citizens. They were deported to Germany, a country they had never known. The historian Professor Peter Stanley considers the way they were treated to be a very strong example of how the intense hatred during the war had a very negative effect in Australia.[44]

Australian trade with Germany and immigration from Germany were banned for the first few years of the 1920s. Jürgen Tampke of the University of New South Wales and Colin Doxford wrote in 1990 in the book Australia, Willkommen that "observers in the German Foreign Office in the years after the First World War were convinced that in all the British Empire the hatred of the 'Huns' was strongest in Australia. Speculating why this might be the case, they thought that the answer could lie in Australia's geographical and cultural isolation from Europe. It was believed that the Europeans, accustomed to centuries of warfare, had been forced to realize that they must overcome the scars of war."[45]

See also: South Australian attitudes towards Lutheran Schooling during World War I (Flinders Ranges Research)

♦ Notes:

1. Leske (1996), / Monteath, Peter (ed.). (2011). Germans: travellers, settlers and their descendants in South Australia. Kent Town (S.A.): Wakefield Press. Introduction, p. X (Roman 10)

2. Voigt (1987), p.65 / Lodewyckx (1932), pp.227-228

3. McKernan (1984), p.263 / Ian Harmstorf, in Prest et al (2001), pp.224-225

4. Blacket (1911), p.105

5. Blacket (1911), p.115

6. Hoyer (2022), pp.120-121, 124, 179

7. Williams (2003), p.19 / Hoyer (2022), pp.140, 155-157, 163

8. Lodewyckx (1932), p.232

9. Leske (1996), p.149 / Lodewyckx (1932), pp.228-229, 232

10. Harmstorf, Ian, in Prest et al (2001), p.225

11. Williams (2003), p.12

12. Göttert, Karl-Heinz. (2017). Deutsche Sprache. 100 Seiten. Ditzingen: Philipp Reclam jun. p.7

13. Lodewyckx (1932), p.237

14. Leske (1996), p.155

15. Harmstorf, Ian (1994). A Trust Betrayed - South Australia's Germans in World War 1. In: Insights into South Australian History, vol. 2, South Australia’s German History and Heritage. Historical Society of South Australia Inc. p.63

16. Alleged German atrocities: Bryce report. The National Archives of the UK government. Archived on 2 Aug 2023. Available online here.

17. Molony, John N. (1987). The Penguin bicentennial history of Australia : the story of 200 years. Ringwood (Victoria) : Viking. p.221

18. Adam-Smith, Patsy. (1978). The Anzacs. West Melbourne: Thomas Nelson (Australia). p.2

19. Lodewyckx (1932), p.236

20. Harmstorf, Ian (1994). A Trust Betrayed - South Australia's Germans in World War 1. In: Insights into South Australian History, vol. 2, South Australia’s German History and Heritage. Historical Society of South Australia Inc. p.67 / McKernan (1984), pp.161-162

21. Gamble, Leo. (2003). Mentone through the years / Leo Gamble ; design by Graham J. Whitehead. Mentone : The author. pp.91-92

22. Tampke & Doxford (1990), p.189

23. Nailon, Brigida. (2001). Nothing is wasted in the household of God : Vincent Pallotti's vision in Australia / Brigida Nailon. Richmond, Vic. : Spectrum Publications. pp.71, 75 / Tampke and Doxford (1990), p.191

24. Meacham, Steve. (2017, July 7). Beagle Bay, Mother of Pearl Church: A piece of Germany, in the heart of the Kimberley. Traveller. In The Sydney Morning Herald. Available online here.

25. McKernan (1984), p.160

26. Connor & Yule & Stanley (2015), p.160 / Harmstorf, Ian (1994). A Trust Betrayed - South Australia's Germans in World War 1. In: Insights into South Australian History, vol. 2, South Australia’s German History and Heritage. Historical Society of South Australia Inc. p.59 / Lodewyckx (1932), p.236

27. ST. KILDA FOOTBALL CLUB. (1914, December 15). The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 - 1954), p. 8. Retrieved March 12, 2023, from <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article190660574> (the change of club colours)

28. FOOTBALL (1914, December 2). Winner (Melbourne, Vic. : 1914 - 1917), p. 8. Retrieved March 12, 2023, from <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article155522774> (a disappointed fan)

29. FERN TREE GULLY SHIRE COUNCIL. (1916, October 20). The Reporter (Box Hill, Vic. : 1889 - 1925), p. 2. Retrieved March 11, 2023, from <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article75166403>

30. McKernan (1984), p.165 - however, Dr McKernan's information (in The Australian People and the Great War) about Matilda Rockstroh's specific workplace is not correct. She did not work in the St Kilda Road Post Office (corner Inkerman Street); she worked from 1915-1918 in the post office that was incorporated into the St Kilda railway station in 1907 - information received from John Waghorn, a private historian of the Victorian postal system. (Personal communication, phone call on 20/01/2014).

31. Helmi, Nadine & Fischer, Gerard. (2011). The enemy at home : German internees in World War I Australia / by Nadine Helmi, Gerard Fischer ; with contributions from Beth Hise, Stephen Thompson, Mark Viner. Kensington, N.S.W. : UNSW Press. p.23

32. Connor & Yule & Stanley (2015), p.152

33. & 34. Harmstorf, Ian (1994). A Trust Betrayed - South Australia's Germans in World War 1. In: Insights into South Australian History, vol. 2, South Australia’s German History and Heritage. Historical Society of South Australia Inc. p.64

35. Connor & Yule & Stanley (2015), p.154

36. Lodewyckx (1932), p.240

37. Thompson, Stephen. (exhibition curator). (2011). The German Australian Community. In: The Enemy at Home. German internees in World War I Australia. NSW Migration Heritage Centre. Available online hier. Accessed 23/08/25.

38. REINFORCEMENTS REFERENDUM. (1917, December 3). The Journal (Adelaide, SA : 1912 - 1923), p. 2 (5 P.M. EDITION). Retrieved August 31, 2025, from <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article201917117>

39. REFERENDUM. (1917, December 3). The Twofold Bay Magnet : and South Coast and Southern Monaro Advertiser (NSW : 1908 - 1919), p. 3. Retrieved August 31, 2025, from <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article217758981>

40. DISFRANCHISED AUSTRALIANS. (1917, December 20). The Australian Worker (Sydney, NSW : 1913 - 1950), p. 15. Retrieved August 31, 2025, from <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article145807014>

41. GOOD ENOUGH TO FIGHT. (1917, December 8). Daily Standard (Brisbane, Qld. : 1912 - 1936), p. 4 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved August 31, 2025, from <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article179433156>

42. McKernan (1984), p.156

43. McKernan (1984), p.263

44. Stanley, Peter, & National Library of Australia. (2017). The crying years : Australia's Great War / Peter Stanley. Canberra, ACT : NLA Publishing. p.216

45. Tampke & Doxford (1990), p.205

♦ References:

Bennett, Robin (1970). Public Attitudes and Official Policy towards Germans in Queensland in World War 1. Honours Thesis, University of Queensland.

Blacket, John & Way, Samuel James, Sir (1911). History of South Australia : a romantic and successful experiment in colonization (2nd edition). Adelaide: Hussey & Gillingham.

Connor, John. & Yule, Peter. & Stanley, Peter. (2015). The war at home. South Melbourne (Victoria) : Oxford University Press.

Harmstorf, Ian (1994). Insights into South Australian History, vol. 2, South Australia’s German History and Heritage. Historical Society of South Australia Inc.

Hoyer, Katja. (2022). Blood and Iron. The rise and fall of the German Empire 1871-1918. Paperback edition. Cheltenham (UK): The History Press

Leske, Everard. (1996). For Faith and Freedom: the Story of Lutherans and Lutheranism in Australia 1838-1996. Adelaide: Openbook Publishers

Lodewyckx, Prof. Dr. A. (1932). Die Deutschen in Australien. Stuttgart: Ausland und Heimat Verlagsaktiengesellschaft.

McKernan, Michael (1984). Manufacturing the war: 'enemy subjects' in Australia. Chapter 7 in The Australian People and the Great War. Sydney: Collins.

Prest, Wilfrid, & Round, Kerrie & Fort, Carol & Wakefield Press. (2001). The Wakefield companion to South Australian history / editor: Wilfrid Prest ; managing editor: Kerrie Round ; assistant editor: Carol Fort. Kent Town (Sth. Aust.): Wakefield Press. pp.224-225

Tampke, Jürgen and Doxford, Colin. (1990). Australia, Willkommen. New South Wales University Press.

Voigt, Johannes H. (1987). Australia-Germany. Two Hundred Years of Contacts, Relations and Connections. Bonn: Inter Nationes.

Williams, John F. (2003). German Anzacs and the First World War. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press