First World War

Internment

During the First World War 6,890 Germans were interned, of whom 4,500 were Australian residents before 1914; the rest were sailors from German navy ships or merchant ships who were arrested while in Australian ports when the war broke out, or German citizens living in British territories in South-East Asia and transported to Australia at the request of the British Government. Some internees were temporary visitors trapped here when the war began. About 1,100 of the total were Austro-Hungarians, and of those around 700 were Serbs, Croats and Dalmatians from within the Austro-Hungarian Empire who were working in mines in Western Australia.

Some people of German descent were interned despite having been born in Australia (and having spent their whole life in Australia). This was the fate of about 70 Australians of German descent. At the Holsworthy internment camp some of these people banded together and formed the 'Association of Interned Australian born Subjects'. They wrote letters to the government protesting about their treatment, and about the injustice of this imprisonment without trial, and about the financial hardship experienced by their wives and children at home, but the government minister was unmoved.[1]

Business Competitors & Union Troublemakers

In World War I the Australian Government wanted to stop companies run by businessmen of German descent from competing with "British" companies, in case companies run by German-Australians could somehow help the German war effort in Europe. An easy way to do this was to intern the directors and managers of such companies, even if they were naturalised British subjects.

Examples:

- Franz Wallach and Walter Schmidt of the Australian Metal Company (subsidiary of a German company) in Melbourne;[2]

- Edmund Resch, the Sydney brewer (who had been in Australia for 50 years);

- Carl Zoeller, a successful and popular member of the Brisbane German-Australian community and importer and maker of medical and surgical equipment;[3]

- Frederick Monzel, publisher and printer of the Queenslander Herald.[4]

Australian workers and self-employed small-businesspeople needed to feel that they were also contributing something to the Empire's war effort - by recommending to the government that a German-Australian be interned they were being patriotic, but naturally they were especially keen to do so if that eliminated one of their competitors in business. In Melbourne, Mr F.W. Abbott, the manager of "The Neway", a clothes cleaning and dyeing company in Little Collins St, sent the government the names of three competitors who he claimed were German. He wrote:[5]

Cannot Germans trading under British names be made to disclose their names? This applies to all classes of business in Australia. There would be nothing harsh about such a regulation if passed as they will still have an open chance to trade and to get business from those people of Australia who are not loyal enough to stick to their own people.

Mr F.W. Abbott

Obviously Mr Abbott's complaint was in his own business interest. A law was introduced prohibiting enemy aliens from changing their names. A Melbourne waiter sent to the authorities a list of names of "enemy aliens" working in various hotels and cafes in the city. Some professors on the council of the University of Melbourne stopped the appointment of two lecturers of German background. Dr Maximilian Herz, Australia's most distinguished orthopaedic surgeon, was interned. He had played a pioneering role in orthopaedic surgery in this country.[6] The Sydney branch of the British Medical Association (as the Australian Medical Association was then known) cancelled the membership of German-born doctors and campaigned to have them deported. They said:

It is not in the public interest that medical men of alien enemy birth and qualification should be allowed to practise in the Commonwealth.

British Medical Association, Sydney

The Sydney branch of the British Medical Association no doubt did not like the fact that Dr Herz had strongly criticised the standards of Australian doctors at various conferences before the war.

In a court case in Temora, western New South Wales, "a British subject" was accused of having used indecent language in the bar of the Empire Hotel. The Police Magistrate dismissed the case because the two witnesses for the prosecution were unnaturalised Germans. He told them:[7]

You and your friend should be interned. It is a public scandal that the Federal Government allows unnaturalised Germans of military age to work among and in competition with British subjects.

Police Magistrate N.A. Ormonde Butler

From this it doesn't seem that a national Australian identity was very developed yet at that time; the bond to Britain was very strong. It was not until 1949 that the Australian Government saw its way to introduce Australian citizenship.

The unions were against Germans in Australian workplaces, whether they were co-unionists or not. The war caused a drop in living standards, higher unemployment and higher prices, and this created hostility to citizens of German origin. In some workplaces Australians refused to work with Germans. The Australian Government saw Germans as troublemakers in workplaces, encouraging strikes in order to weaken the war effort of the Empire and help Germany.

Examples:

Ernst Buchwitz, a worker at the Baffle Creek Sugar Mill near Bundaberg and an organiser for the Australian Workers Union, was interned and later deported for having "caused disruption between the men and the mill", a charge Buchwitz denied.[8]

Friedrich Striowski had arrived in Australia in 1876 at the age of 14 and was naturalised in 1904 (naturalised = they had taken an official oath of allegiance and become British subjects/citizens of Australia; Australian citizenship did not exist until 1949). In early 1915 Striowski's wife Katherine wrote to the Minister of Defence asking for financial assistance for her seven children, because her husband 'had been thrown out of employment by his fellow union men on the Melbourne Wharf after many years in the Union'. The authorities investigated and saw that the family was in hardship and arranged a military permit for Striowski to work on the docks. Presumably the atmosphere on the docks was still hostile because even with the permit it seems that Striowski still could not find stable work and as he had no money he went into voluntary internment on 23rd June 1915. On the same day that he became a voluntary prisoner-of-war his oldest son departed for Egypt with the Australian army. Would Striowski's former workmates on the Melbourne Wharf have been more welcoming of him if they had known that his son was in the Australian armed forces overseas?[9]

C.S. Schache, a waterside worker in Gladstone, Queensland, and "a second-generation Australian with a German grandfather", was interned because he was the local secretary of the Workers' Political Organisation.[10]

Willy Gubba in Melbourne was interned because he was a member of the Australasian Socialist Party. He was a waiter in a restaurant owned by a German-Australian, and it was said that the restaurant was used by "all the Germans in and around Melbourne of all classes", according to the detectives who investigated for the Defence Department. There was no evidence, but the detectives concluded that "Probably Gubba as a 'mere waiter' was used as a tool for the other Germans of higher standing and financial position" and the restaurant "was the channel used by the financial opponents to assist the socialists in putting up such a sustained fight against conscription".[11] The Australian Government believed there were German spies all around the country.

Internment of the leaders of the German-Australian Community

The Defence Department had a deliberate policy of interning those whom it decided were leaders of the German-Australian community, especially in South Australia and in Queensland, the states with the highest proportion of people of German background, and states in which there were distinctive areas of group settlement (though by 1914 the German-Australians were in the minority in many of these areas). The government wanted to destroy the German-Australian community as a distinct socio-cultural element in Australian society. With this aim, German clubs were closed, Lutheran schools were closed in many places (all of them in S.A. were closed), and the leaders of the community were interned.

Consuls and pastors

Apart from business leaders, the Defence Department saw the consuls and pastors as the leaders in the German-Australian community. The five consuls who were interned in Australia were not professional diplomats, they were honorary consuls, and most were naturalised British subjects. The five were: Eugen Hirschfeld from Brisbane, Ludwig Ratazzi from Perth (of German and Italian background; he was Consul for both countries), Alfred Christian Dehle from Hobart, Otto Johannsen from Newcastle, and Wilhelm Friedrich Christian Adena from Melbourne. As prominent businessmen, their business activities were seen as harmful to British-Australian interests. In South Australia, Consul Muecke was interned for a short time at Fort Largs in April 1916, then from May to October he was under detention in his own home with military guards while his youngest son was fighting in France with the Australian Army after being wounded earlier at Gallipoli.

In South Australia Pastor Nickel was interned for a short time, but no other pastors were after that. In Queensland nine pastors were interned, six of whom were naturalised British subjects. Two of those had been born in Australia, including Pastor Friedrich Gustav Fischer of Goombungee. He had been born in South Australia in 1876, and both his parents had also been born in South Australia. Federal Cabinet approved Fischer's internment on the basis of an intelligence report (can 'intelligence' be the right word?!) from the Defence Department which included:[14]

The situation in the German districts gives great anxiety to British residents, and the best way of relieving their anxiety, as well as of keeping German residents in check, is to intern occasionally a few leading German residents. From this point of view it is considered that the internment of Fischer would be justified.

(One can see how society in Australia at that time still felt "British" rather than Australian.)

The Camps

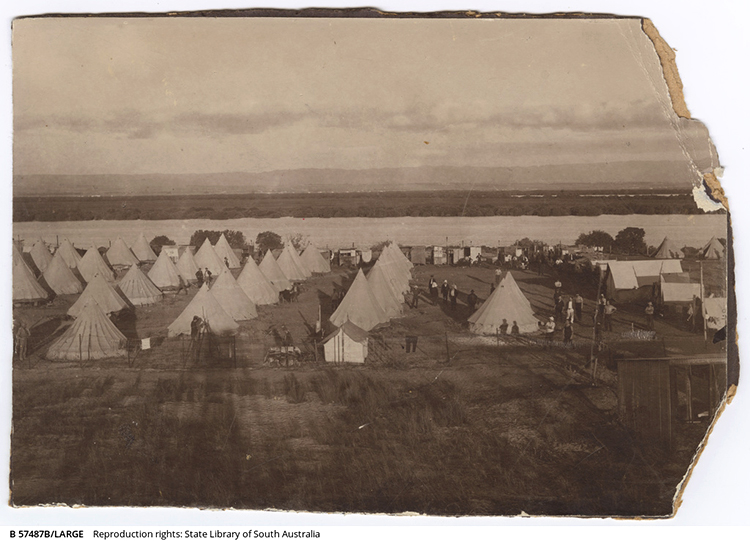

Torrens Island internment camp, S.A.

Photographer: Dubotzky, Paul. State Library of South Australia, B 57487B

Soon after the war started, the Australian government had to set up accommodation for the large number of people who were being interned, so concentration camps (an idea first used by the British Government in the Boer War 1899-1902) were established in each of the six states. In three states (Tasmania, S.A. and W.A.) they were on islands a short distance from the capital city. By the end of May 1915, almost 3,000 people had been interned.

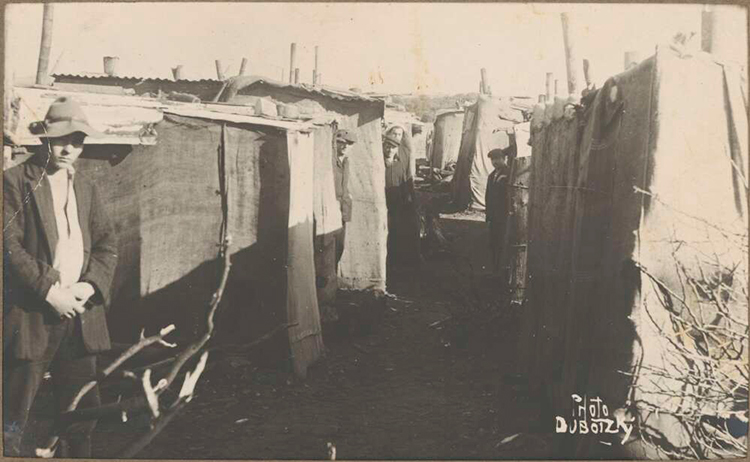

Torrens Island internment camp, S.A.

Photographer: Dubotzky, Paul. National Library of Australia, nla.obj-141208822

| Internment camp | Internees |

|---|---|

| Enoggera, Queensland (suburban Brisbane) | 137 |

| Holsworthy, NSW (south-east of Liverpool) | 1342 |

| Langwarrin, Victoria (south-east of Melbourne) | 420 |

| Torrens Island, S.A. (in the harbour of Port Adelaide) | 355 |

| Rottnest Island, W.A. (Indian Ocean, near Fremantle) | 628 |

| Bruny Island, Tasmania (south of Hobart) | 58 |

| TOTAL | 2940 |

Two months later the decision was made to close these regional camps and transfer the prisoners to concentration camps in NSW. Perhaps this decision was made in order to save costs (for example, in all camps Australian soldiers who worked as guards had to be paid), in order to make communication between the camps and Melbourne headquarters easier, and to make sure that all guards treated prisoners according to the rules. There had been complaints that guards on Rottnest Island had often used bayonets on prisoners, and on Bruny Island the prisoners had gone on strike, and an official enquiry had been set up into a scandal involving the flogging of prisoners on Torrens Island.

For this centralisation of the internees, the Holsworthy camp was greatly enlarged, and two special camps were also established in NSW, both in jails that were no longer used. The first, at Berrima (130 km south-west of Sydney in the southern highlands), was mainly for ships' officers and sailors, and the Trial Bay camp (on the NSW north coast) was for about 500 internees, most of whom had been deported from British territories in South-East Asia and the Pacific Islands.

Although the internees were predominantly men, there were exceptions: German families who had lived before the war in areas under British control (or which came under British control during the war), such as Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Singapore, Hong Kong, British North Borneo, Fiji and the German colonies in the South-West Pacific, including New Guinea. The authorities did not want to separate these families and interned them in Bourke, a town in the outback of New South Wales, about 800 km northwest of Sydney. Some families were housed there in the Empire Hotel, but at that time Bourke was a town in decline and there were several vacant houses that the interned families could use. The internees found the heat, dust and flies in the area very unpleasant (Georg Krafft, the former German consul in Fiji, died there in February 1918 of heatstroke), and later in 1918 these families were transferred to a new internment camp in Molonglo near Canberra.[15]

For many internees the long-distance journey from their regional camp to their new camp in NSW was unpleasant. Many complained about rough treatment by police or military officials. Many were handcuffed during their train journey; being treated in public as if they were criminals would not have been pleasant. The luggage of many prisoners was lost en route, and some found that their luggage had been forced open and things had been stolen. The officers and naval internees at Berrima led relatively comfortable lives, but the conditions were dusty and harsh for those at Holsworthy, where they lived in open-sided canvas huts.[16]

Internment Camp, Holsworthy, NSW. Around 1917.

National Library of Australia, nla.obj-141210221

Holsworthy was the largest and longest-running internment camp. It began as a collection of tents and grew into a small town featuring theatres, restaurants and other small businesses, along with an orchestra and sporting and educational activities. The camp was overcrowded and there were only basic washing and toilet facilities.[17]

German gymnasts performing on vaulting equipment outside at the internment camp at Holsworthy, New South Wales, 1918 or 1919. The German prisoners were keen on gymnastics.

Photographer: Carl Schiesser. National Library of Australia, nla.obj-153410976

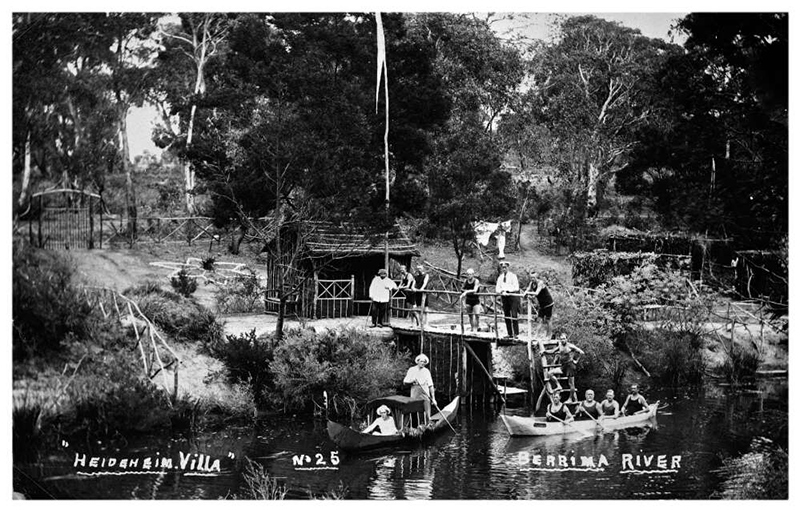

In the camps the internees arranged their own entertainment and many cultural and sporting events. They formed choirs and orchestras, and had theatrical productions. Dr Maximilian Herz directed many successful productions at Trial Bay. At Berrima the sailor prisoners built many different model boats and had regattas and boat exhibitions on the Wingecarribee River.[18] At one exhibition early in 1918 the local public were surprised to see a Venetian gondola, a scale model of the sailor-training ship Preußen, a Chinese junk and a submarine. The Berrima prisoners were also allowed to work for money on local farms.

German internees boating on the Wingecarribee River at Berrima in NSW. These naval internees used their creative skills to build structures like small jetties on the banks of the river. Heideheim Villa is a deliberately ironic name for the small building behind the timber jetty in this photo.

Picture source: Speer, D. (1914). Heidheim Villa, Berrima, New South Wales, ca. 1917. Retrieved September 30, 2025, from the National Library of Australia.

After the war, a difficult problem arose with the nearly 7,000 people held in internment camps in Australia who had been born in Germany or were of German background. As soon as ships were available, about 5,200 of them were deported to Germany. This included some people who had arrived from Germany as babies and who had later become Australian/British citizens. They were deported to Germany, a country they had never known. The historian Professor Peter Stanley considers the way they were treated to be a very strong example of how the intense hatred during the war had a very negative effect in Australia.[19]

♦ Notes:

1. Monteath (2018), pp.34-35

2. Fischer (1989), pp.70-71, 93

3. Fischer (1989), pp.93, 120

4. Fischer (1989), pp.93, 119, 310

5. Fischer (1989), p.94

6. Fischer (1989), p.248

7. Fischer (1989), p.95

8. Fischer (1989), p.97

9. Monteath (2018), p.14

10. Fischer (1989), p.97

11. Fischer (1989), p.97

12. Descendants of William Silas Pearse. (March 19, 2020). <https://freotopia.org/people/pearsegenealogy.pdf> pp.13-16, 23-26 / Scates, Bruce. & Wheatley, Rebecca. & James, Laura. (2015). 'The hands of our own men', Daisy Schoeffel. In: World War One : a history in 100 stories. Melbourne (Vic.) : Viking, an imprint of Penguin Books. pp.212-214 / Monteath (2018), p.53

13. Leggett, C. 'Hirschfeld, Eugen (1866–1946)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, <https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hirschfeld-eugen-6683/text11525>, published first in hardcopy 1983, accessed online 10 October 2025 / Monteath (2018), pp.96, 98.

14. Fischer (1989), pp.102-103

15. Monteath (2018), p.16

16. Stanley (2017), p.85

17. World War I: German internment camps in Australia in pictures. (2014, 29th August). ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Online at: <www.abc.net.au/news/2014-08-05/world-war-i-german-internment-camps-in-australia/5646636> Accessed 31/10/2018. / Tampke & Doxford (1990), p.193

18. Fischer (1989), pp.234-236 / Tampke & Doxford (1990), pp.195-197

19. Stanley (2017), p.216

♦ References:

Fischer, Gerhard. (1989). Enemy aliens: internment and the homefront experience in Australia. 1914-1920. St Lucia (Qld): University of Queensland Press.

Monteath, Peter. (2018). Captured lives : Australia's wartime internment camps / Peter Monteath. Canberra, ACT : NLA Publishing

Stanley, Peter, & National Library of Australia. (2017). The crying years : Australia's Great War / Peter Stanley. Canberra, ACT : NLA Publishing.

Tampke, Jürgen and Colin Doxford. (1990). Australia, Willkommen. New South Wales University Press.