South Australia

The emigration of Kavel's group to South Australia

The villages of Tschicherzig, Klemzig and Kay (where Pastor Kavel's emigrants came from) were small villages in Prussia (Prussia doesn’t exist any more, but it was an independent German state in the northeast of Europe). All of those villages are now part of Poland, because of national border changes at the end of World War II. The immigrants who came to South Australia were mainly farming people and tradespeople.

Why they came

However, they were also very moral and religious people and strictly maintained the traditional practices of the Lutheran church, and didn't wish to give them up for the Prussian king. King Friedrich Wilhelm III was a pious Christian and member of the Reformed (Calvinist) church (his wife Luise was a Lutheran). The big majority of his subjects in the Prussian territories were in Lutheran congregations. Like other kings and aristocrats of that time, Friedrich Wilhelm was also no friend of democracy, and wanted to emphasise the strong authority of the monarchy, even in religious affairs. He decided that all Protestants in the Prussian territories should belong to the same state church. Friedrich Wilhelm wanted to unite the two main Protestant churches (the Lutheran church and the [smaller] Reformed church) in a united Prussian state church. Under Friedrich Wilhelms supervision a new order for church services (Agende) was produced, which all Protestants in Prussia had to use.

Some people refused to give in to this and gave passive and "spiritual" resistance. The king made this new Lutheranism more or less a state religion and the church pastors were in effect public servants, working for the government. Under the law, pastors who continued to run church services using the "Old Lutheran" prayer book and style of worship could be dismissed from their positions (and even be put in prison), and have their property confiscated. The minority of people wanting to hold their church services in the old Lutheran way had to do this in secret. These people were known as Old-Lutherans. For a while, a few pastors had to move around the country carefully, hiding from the police, and had to hold prayer meetings for people at night in forests. Therefore these people were keen to go to a country where they could have freedom of worship.

Religion was not their only reason for wanting to emigrate. Some of them were motivated by economic reasons also. The population of Germany was growing rapidly, meaning there were more people than the amount of work available, and two very bad harvests there in 1844 and 1846 made life for poor people very tough. The German states at that time were still pretty much a farming economy.

How they came to South Australia

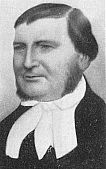

Pastor Kavel

Pastor Kavel made enquiries through the port city of Hamburg about the possibility of emigrating to Russia, to join the large number of Germans living there in the region of the Volga river, or to the United States of America, where many Germans had also gone. Nothing came of this. Kavel went to London and met George Fife Angas, a wealthy Scottish businessman and chairman of the South Australian Company. He was genuinely keen to help people as well as develop the Colony of South Australia, and was impressed by reports about these Germans who wanted to settle in another country. They were said to be religious, self-sufficient, hard working farming people of high moral standards. Angas was a very religious man himself. He offered Kavel and his people a good land deal in South Australia and did everything he could to help arrange the emigration.

The Old-Lutherans applied to the Prussian government for permission to emigrate, but the government delayed for two years. The emigrants again and again put in new applications and tried to explain as humbly as possible why they wanted to leave. George Angas sent his secretary Charles Flaxman to Prussia to try to persuade the authorities to issue emigration permits. It is not clear whether the Prussian Government's reluctance to issue visas was due to real concern about the fate of the emigrants in travelling to a far-away, pretty unknown continent (this is what the Government officials often emphasised), or due to the Government's irritation at the stubbornness of the Old-Lutherans, whose emigration might make the world think that Prussia was oppressing people's religious beliefs.[1]

Eventually permission was given. The emigrants had to travel to the port of Hamburg from their inland villages by barge along rivers, as railways had not yet been built. These barges were commonly called Oder barges. The journey along four different rivers (Oder, Spree, Havel and Elbe) and on the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Canal that connected the Oder and the Spree rivers, was about 600 km long and took three weeks. The following map shows the route they took:

From Brandenburg to Hamburg harbour

(from: Schubert, David. (1997). Kavel's People, with the author's permission)

When the emigrants’ barges stopped overnight in Berlin quite a lot of people came to check them out and listen to their religious singing. Some onlookers ridiculed them (“why leave your homeland because of religious differences?”) and others admired them for their singing and for their steadfastness in being prepared to emigrate to the other side of the world.[2] The Prussian king was not impressed – he felt it was something of an insult that these people wished to leave their homeland allegedly due to religious persecution (and that they were attracting so much public attention). In the royal dining room at the City Palace in Potsdam he said:[3]

Don’t want to hear about it; it’s too unpleasant. Outrageous in a country where freedom of religion and conscience prevails. But freedom does not mean the complete absence of discipline, undermining public order and rejecting obedience. These deluded people call themselves Lutherans. What would Luther say if he were alive today? Be that as it may. I wish them well!

Friedrich Wilhelm III., King of Prussia 1797-1840

While the emigrants waited in Hamburg to be able to board their ship for Australia, many of the Hamburg locals were curious about them and what they were doing, leaving Germany for the other side of the world because of their beliefs. A Hamburg Senator, Hudtwalcker, was impressed by them and wrote a description of Kavel's people in a newspaper.

See Pastor Kavel's grave and memorial in Tanunda, South Australia, as well as examples of present-day recognition of his achievements and status.

Explanation of terms:

The Lutheran church is a "Protestant" church which developed out of the ideas of Martin Luther. He protested in the 1520s about the way in which the Catholic church operated in Germany at that time. He was also the first person to translate the Bible into German, so that people could read it without having to be able to read Latin.

The Reformed church is also based on the ideas of Martin Luther, but doesn't put as much importance on church services run according to strict worship rituals and on majestic church buildings. The organisation of their church is not so hierarchical as with the Lutherans.

Agende = worship book, an official book prescribed for use in church, containing all the worship orders, Bible readings and prayers. In 1830 King Friedrich Wilhelm's new worship book was introduced into and made compulsory for all Protestant churches in Prussia.

♦ Notes:

1. Tampke & Doxford (1990), p.27

2. Lodewyckx (1932), pp.37-38

3. Voigt, Johannes H. (1987). Australia-Germany. Two Hundred Years of Contacts, Relations and Connections. Bonn (Germany): Inter Nationes. p.18

♦ References:

Leske, Everard. (1996). For Faith and Freedom: the Story of Lutherans and Lutheranism in Australia 1838-1996. Adelaide: Openbook Publishers. pp.21-28

Lodewyckx, Prof. Dr. A. (1932). Die Deutschen in Australien. Stuttgart: Ausland und Heimat Verlagsaktiengesellschaft. pp.37-40

Tampke, Jürgen and Colin Doxford. (1990). Australia, Willkommen. Kensington (NSW): New South Wales University Press. pp.28-31

Van Abbè, D. (1967). Kavel, August Ludwig Christian (1798–1860), Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1967, accessed online 4 August 2022.